The Freaky Way Facebook Learned Every Single Thing About You

Once upon a time—like, for a couple years in the mid 2000s—Facebook was fun. You posted emo song lyrics as your status jic somebody you wanted to impress popped by your profile page. You uploaded party photos from your ~*fancy new*~ digital camera in batches of, like, 500, blissfully unaware that these pics would follow you around the rest of your life. Remember the bubbly thrill of being “poked” by your actual friends? Good times.

Then your entire extended family joined and started spamming you with friend requests. And everybody got obsessed with Farmville. Oh, and your personal data morphed into a product while you weren’t paying attention, while private groups became petri dishes for hate groups and misinformation. And now, somewhere, on someone’s Newsfeed, at any given second, anti-vax content—and beyond that, an entire universe of fake facts—is running rampant.

What exactly happened over the past 17-odd years behind-the-scenes that deposited us in this messy moment? In An Ugly Truth: Inside Facebook’s Battle for Domination, New York Times reporters Sheera Frenkel and Cecilia Kang trace the evolution of the social media network, revealing, through deep investigatory work, the power the platform holds over our lives.

“What we really wanted to do is show you that, once you open the app, there is a massive machinery and a company culture that the public really needs, and deserves, to understand,” Kang told Cosmopolitan during an interview. “It’s been a journey from the silly, fun Facebook that people experienced to the revelations of harms and dangers.” Here, she explains what the quest has really meant for its billions of users.

One concept that comes up in the book early on is that Facebook prioritized “engagement above all”—can you elaborate?

In the book, we have an anecdote about how, even at Harvard, Mark Zuckerberg told classmates that what he wanted was to have people go onto The Facebook (which is what it was called at the time) and mindlessly scroll. To just be on. Because the more you’re on, the more Facebook knows about you. So he understood, even in those early days, how powerful engagement was, because engagement led to more data; he knew that was going to be the power of social media. So as the company developed more tools, it was about amping up and encouraging engagement.

The best example of that was the creation of the Newsfeed, in 2006: It was then that Facebook realized they didn’t want people to just visit each other’s static pages—they wanted, almost like a ticker tape, for things to be constantly scrolling. Because it would make you want to continually watch and come back for more. But also, the company knows that emotive content inspires engagements. Things that make you scared, angry, happy—those are things that make you come back, which feeds the Facebook profit machine.

What should people better understand about that “machine?”

So, Facebook is an advertising company. Advertisers want to know Facebook’s users better, and Facebook users help advertisers get to know them better by sharing more, posting more, connecting more. Every single stroke of the keyboard, every single thing you hover on, every share: It’s all collected into this massive reservoir of information about [you]. Advertisers need this information so they can be even more sophisticated in their ability to target you, the potential consumer. And Facebook profits because it sells this data to advertisers.

What would you say to people who don’t have a problem with being targeted?

Two things: One, it’s important to know that Facebook and these brands know so much about you that not only do they know your particular profile but also enough to predict things about you. They can say, “Based on our GPS location tracking of the [Facebook] app, we know this person went to this area and this area; we know they’ve been hovering, looking at things like baby clothes and prenatal vitamins, so this person is probably pregnant”—that’s the level of predictive analysis.

Every single stroke of the keyboard, every single thing you hover on, every share: It’s all collected into this massive reservoir of information about you.

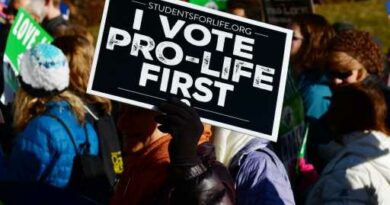

This model is so new that we don’t really know what it all means. There are examples already of that kind of information being used negatively, to target discriminatively. Facebook has been involved in a lawsuit—it settled—where discriminatory ads were being placed for housing based on demographic profiles of Facebook users. And it’s not just commercial brands that advertise: It’s all kinds of interest groups, public advocacy groups, politicians. It’s also important to know that anti-vaccine ads, which were only banned recently, were reaching the kinds of audiences that [Facebook] knew would be receptive.

So…what can we do, as users?

We aren’t advocating for people to quit Facebook—we don’t think it’s realistic. Also, even if you do, Facebook owns Instagram and Whatsapp; Instagram is growing and WhatsApp is globally ubiquitous, and a lot of the same problems exist on both of those apps. What people really need to do is to be informed, to understand, to think twice about how the algorithms work. To pause for a second before sharing something on Facebook. To ask themselves: Where is this source coming from? Is it authoritative? If I’ve never heard of it before, maybe I’m not going to share it. And maybe I’m not going to believe it.

Also, self-check: How do I feel about my data being used, and me essentially becoming the product for Facebook? Maybe you’ll think differently, maybe you won’t. But we have to be more informed, as users and as citizens, to think about our role in this ecosystem of spreading information that is oftentimes harmful or false.

Developing media literacy on a massive scale sounds… tough.

The individual responsibility is one piece. The other piece is that there has to be some sort of regulatory oversight. I think Facebook accepts that themself: They say they want to have regulation…but change is not going to come from within Facebook, at least not with the current structure that’s there. A check has to come from outside, on the privacy front about how much data can be used and how it’s used, and potentially from the speech front—that’s going to be really tricky.

Are you hopeful?

I mean, it’s hard: If you talk to some super smart people like Shoshanna Zuboff, who wrote The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, she’s like, “Nothing can change unless we address the business model, because that’s the root.” Governments really need to understand how algorithmic amplification works, how data collection works, how the business of behavioral advertising works, and how that can be so opaque and complex. But to answer your question…yes, I think so?

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Source: Read Full Article