30 years after Rodney King, Derek Chauvin trial is ‘like reliving history’ for lawmakers, lawyers, activists and others who were there

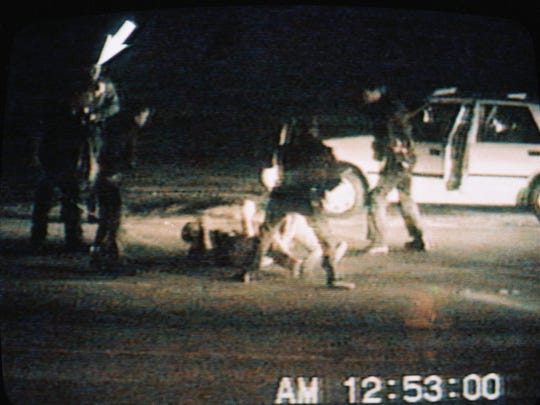

Four white police officers surround a Black man as he is harmed. An amateur video is shot of the encounter. The footage goes viral, prompting massive unrest and calls for social reforms.

Three decades before George Floyd died under the knee of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, whose trial is underway, a similar recorded moment unfolded in Los Angeles as police batons rained down on Rodney King, 25.

The beating of King 30 years ago this month, captured on a Sony Video8 Handycam by a plumber named George Holliday, was a watershed moment in the nation’s fraught history of race relations, one many assumed would lead to guilty verdicts for the officers. Black Americans were familiar with police brutality, but now the rest of the nation could see it with their own eyes.

A year later, the trial was moved from racially diverse downtown Los Angeles to the primarily white suburban enclave of Simi Valley. The mostly white jury acquitted the officers, and largely Black South Los Angeles exploded in violent uprisings that claimed more than 60 lives, injured nearly 2,400 and caused about $700 million in damage.

A peaceful vigil is held at the George Floyd memorial at the Cup Foods Market in Minneapolis on June, 1, 2020. Floyd died in police custody on May 25 at this location. (Photo: Jack Gruber, USA TODAY)

For those who lived through the King trauma – a mix of activists, politicians and attorneys reached by USA TODAY – there is a deep concern, not only that the intervening years have brought little change to policing practices but also that the Chauvin case could offer a painful repeat of the past.

“When I look at what’s happening in Minneapolis, I see LA in 1992, so it’s like reliving history again,” said Zev Yaroslavsky, 72, a longtime politician who was a Los Angelescity councilman at the time.

Of Floyd’s death, Yaroslavsky, director of the Los Angeles Initiative at the University of California, Los Angeles’ Luskin School of Public Affairs, said, “What happened that instant, on that sidewalk, at that moment, that was not a one-off. It’s a story that has replayed itself for decades, over and over again.”

What may also repeat itself – despite the presence of a nine-minute cellphone recording of Floyd saying, “I can’t breathe” and asking for his mother before dying – is a verdict that many in communities of color would find unsatisfying, especially now that Chauvin attorneys requested a continuance and change of venue after Floyd’s family received a $27 million settlement from the city of Minneapolis.

Chauvin faces charges of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter.

“I can see charges for an offense less than murder resulting here, which is not what I’m advocating for in the least,” said John Burris, an Oakland, California-based attorney who was among the lawyers who represented King in 1992 in his civil trial against the city of Los Angeles, which awarded King $3.8 million in damages.

Congresswoman Karen Bass, who represents some of the same parts of Los Angeles that exploded after the King verdict, said she “wondered again if this will be a moment we finally recognize what has been going on for generations and will we be able to bring about change? I still have that question mark with me. Will this trial produce justice? Will that video be enough?”

Bass said she hopes Congress will pass her George Floyd Justice In Policing Act, which aims to, among other things, hold officers more accountable for their actions. It passed in the House this month but needs Senate approval.

She said she is concerned that a disappointing verdict in the Chauvin trial may rip open old wounds. Even though the King beating was videotaped, “that didn’t produce justice,” said Bass, 67. “It was a profound feeling of overwhelming grief and sadness that it doesn’t seem to matter.”

A death that sparked a rebellion

Floyd had been trying to turn his life around when he encountered Chauvin shortly after a store clerk called police, alleging that Floyd had tried to pass off a fake $20 bill.

The 46-year-old Texas native had a past that included a college football scholarship, hip hop aspirations and volunteerism at a church, along with multiple run-ins with police, drug addiction and time in prison for armed robbery.

Chauvin pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck as the handcuffed man beneath him protested he could not breathe. Three other officers helped restrain Floyd and onlookers who pleaded for them to get off Floyd.

In the aftermath of Floyd’s death, protests spearheaded by organizers in the Black Lives Matter social justice movement and other activist groups raged across the nation, most peaceful, though others resulted in violence and looting that sometimes involved individuals who were not part of the protests.

Burris, 75, said he hopes things remain calm in the wake of a Chauvin verdict.

“You don’t want other people to die or wind up in jail as a consequence of any verdict, because then nothing is gained,” he said. “With Floyd’s death, there were protests that included whites and others all over the country. Everyone who saw that video knew what they witnessed was wrong. You didn’t have that sort of universal feeling with King.”

If you fast-forward the videotape of history since King was beaten, other Black people have died at the hands of police, some caught on cellphone videos, others not. Their names include Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile and Breonna Taylor.

Nadine Seiler attends a Martin Luther King Day demonstration Jan. 18 at Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington. (Photo: Jarrad Henderson, USA TODAY)

That saturation has had its effect, said Steven Lerman, 70, who was King’s main attorney during the civil trial and could often be seen by his side at news conferences.

“Society has changed, but in a way, it’s deadened our senses,” he said. “The King case was a shock, like putting your fingers in a socket. But since 1991, it seems blue on Black violence has escalated, and many people are numb.”

Todd Boyd, a professor of critical studies at the University of Southern California, said the country has made some progress since 1992, notably in the election of a Black man as president, Barack Obama, and a Black woman as vice president, Kamala Harris.

“But we’re still having the same conversation people were having in the early ’90s and even before then,” he said. “The fact that we need to reference Rodney King and the riots to talk about George Floyd says in one sense that we have not made progress.”

‘The full glare’ of police violence on video

It is hard to understate the impact of the King video in an age well before the ubiquity of cellphones and the internet. Grainy and raw, it captured a scene that for many Black Americans was painfully familiar, if publicly invisible.

Early in the morning of March 3, 1991, King and two friends wrapped up a night of partying and basketball watching and hopped into a car to head home.

Their speeding vehicle quickly caught the attention of California Highway Patrol officers. The chase moved onto city streets and drew police helicopters. The car finally was pulled over, and the occupants were told to get on the ground.

Several buildings are fully engulfed in flames in Los Angeles in April 1992 during the Rodney King trial uprisings. (Photo: Reed Saxon, AP)

Holliday heard the commotion. He walked to the balcony of his Lake View Terrace apartment and switched on his camcorder, which he had used to film a nearby night-time movie shoot involving Arnold Schwarzenegger and his “Terminator” film series. Holliday’s video shows a Tasered King being beaten repeatedly by officers before being handcuffed.

After initially failing to get the news media interested in his tape, Holliday got a TV station to play a short clip of it days later. The result was instant and electric, said Danny Bakewell, 75, a longtime activist who owns two newspapers, the Los Angeles Sentinel and the L.A. Watts Times.

After watching the news broadcast of Holliday’s video, Bakewell called Los Angeles City Council members, friends and other activists.

“We were aware of being treated that way, but this was the first that it was recorded in the full glare of light, that’s what made it so shocking,” he said.

Boyd, the professor, was in a hotel room preparing for a job interview days after the police beat King.

As he ironed his pants, he turned on the news and watched in disbelief as a white man being interviewed explained that the cops wouldn’t have beaten King unless he was guilty.

“I was like, this guy is not only expressing his opinion, but he’s expressing the opinion of a lot of people,” he said. “And when I heard that, there was something about it that said to me the cops are going to get off.”

On May 1, 1992, Rodney King pleads for the end of rioting and looting that plagued Los Angeles after the verdicts in the trial of four Los Angeles police officers accused of beating him. It was King's first public appearance since the beating a year earlier. (Photo: David Longstreath, AP)

On April 29, 1992, after seven days of deliberations, a jury voted to acquit the four officers involved in King’s beating largely on the grounds that his resisting arrest prompted their actions.

Bass,a community activist, headed to a church in Los Angeles to help plan a response, not realizing that in parts of the city where most Black people lived, chaos had erupted.

Bass drove through the intersection of Florence and Normandie avenues minutes ahead of a colleague whose car was hit by rocks, the same intersection where truck driver Reginald Denny was later hauled out of his cab and beaten almost to death before being rescued by four good Samaritans.

At the church, the atmosphere was funereal. Bass recalled people asking, “Will we ever, ever get justice in the United States.”

Manuel Pastor, 64, then a professor at Occidental College in Los Angeles, was on campus when he heard the verdict. He remembered an “eerie stillness,” then a profound fear that things would soon erupt.

Pastor, who serves as director of the University of Southern California’s Equity Research Institute, went into a courtyard where students had started to gather. Some were in shock. Students of color were grieving. Outside, there was so much smoke from fires that the plumes blocked the sun.

He remembers feeling like, “Oh my God. It’s going to be open season on Black and brown people.”

Despite years of working with the New Majority Task Force, a coalition aiming to bring together Black, Latino and Asian groups around economic issues, Pastor recalled feeling “pretty shattered by the civil unrest.”

Flying into Los Angeles from Chicago that night, songwriter and activist Jay King – no relation to Rodney King – noticed strange patches of orange dotting the urban tapestry below the clouds. In a matter of hours, large parts of Los Angeles were in flames.

The next day, King went to friends’ Black-owned restaurant and ate eggs over easy, turkey sausage, wheat toast and hash browns. No one touched the eatery, but looters attacked nearby Korean-owned businesses while police officers drove by.

In this April 29, 1992, file photo, people enter and leave a swap meet in Los Angeles. Violence broke out in the area after four Los Angeles police officers were acquitted on all but one charge for the videotaped beating of motorist Rodney King. (Photo: Reed Saxon, AP)

King, 59, said some community members had issues with Korean Americans who owned a number of neighborhood stores.

“You could just feel the tension, the hate, the racial conflicts,” he said. “It’s all thick in the air.”

Edward Chang,at the time an assistant professor at California State Polytechnic University in San Luis Obispo, California, recalled turning on the television and being horrified by what he saw.

“It was like watching a war,” said Chang, 64, a professor of ethnic studies at the University of California at Riverside and founding director of the Young Oak Kim Center for Korean American Studies. “It was a nightmare. People’s lifetime savings became ashes overnight.”

The financial damage of the riots in Koreatown was estimated at $400 million. Chang said the experience served as a “wake-up call” that launched political activism that helped place Korean Americans on city councils, school boards and state Legislature posts.

“It’s been major progress,” he said.

After the acquittal of the four officers, attorney Lerman called King, whom he always called Glen, his middle name.

King was livid when he heard about the verdict. “But I said, ‘Glen, you’ll do better now in the civil case, given these four guys got off,’” Lerman said. “And that’s what happened.”

In a negligence claim, King’s team successfully argued that his encounter with four Los Angeles Police Department officers – Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, Theodore Briseño and Rolando Solano – was a civil rights violation that resulted in 11 skull fractures, permanent brain damage, broken bones and teeth, kidney failure and emotional trauma.

A California Highway Patrol officer stands guard in Los Angeles as smoke rises from a fire down the street April 30, 1992, the second day of unrest after the acquittal of four Los Angeles police officers in the Rodney King beating case. (Photo: David Longstreath, AP)

By contrast, in the criminal trial, the officers’ defense team convinced the jury that King was in an altered state and had aggressively resisted arrest, particularly during parts of the encounter that occurred before Holliday captured the violent scene with his camera.

After a brief moment of celebrity anchored by his famous plea, “Why can’t we all just get along?” King wrote a memoir, battled addiction and was found dead in his swimming pool in 2012. His daughter Lora King, 37, runs the Rodney King Foundation, a social justice advocacy group.

Floyd video poised to play a critical trial role

The legal maneuverings in the King case could shape the outcome of the Chauvin trial, said some of the lawyers involved in those proceedings.

In 1992, Los Angeles attorney John Barnett represented one of the four officers in the King case, Theodore Briseño. He said the Holliday video “created, in my view, a false belief on the part of the public that the guilty verdicts were preordained, so there were very high expectations.”

On March 15, 1991, CBS aired footage of the Rodney King beating that occurred earlier that month in Los Angeles. (Photo: -, CBS via AFP/Getty Images)

Barnett said the threat of violence or ostracization could influence jurors’ decisions in the Chauvin trial.

“We’re way past the part where we can assume jurors will decide cases based just on the facts, we have to predict they also will be influenced by the consequences of their verdict, and that’s contrary to our entire judicial system,” he said.

Another area of concern, experts said, is the $27 million settlement received by Floyd’s family members. That news resulted in the dismissal of two seated jurors in the case because they reported being aware of the settlement and said they could no longer be impartial.

King attorney Lerman said he is surprised the judge in the Floyd case did not copy the King script and ensure that the civil trial was delayed so its verdict wouldn’t affect Chauvin’s criminal trial.

Lerman said another possible unintended consequence of the Floyd civil trial award could be a jury that is less inclined to deliver the maximum penalty against the officer, given the family has been financially compensated.

“That settlement communicates to the jury that as far as the city’s concerned, he is guilty as hell,” he said.

Whichever way things go in the Chauvin trial, those who vividly recall the King beating and trial said it is important to keep pushing for societal change even if it appears that the past 30 years have been discouraging on that front.

Songwriter King is preparing to vent any forthcoming frustration creatively. King’s R&B group Club Nouveau tackled the Rodney King incident in its music, and he said he plans to release music soon that will incorporate his feelings about the Chauvin case.

Surveillance video shows the early moments of George Floyd's fatal encounter with Minneapolis police in May 2020. (Photo: DRAGON WOK)

“Anger isn’t going to win this,” said King, president of the California Black Chamber of Commerce. “We have to have the race issue conversation if we’re going to move forward. If America is going to be great for once, then she’s got to be fair to all her people.”

Pastor, of the University of Southern California, said communities of color should focus on what changes are needed for the long haul, including police reforms and economic development initiatives, although he acknowledges “that’s a tremendous discipline to have because I know that people will be angry, particularly if the verdict has something that has elements of acquittal to it.”

Former King attorney Burris urged those fighting for justice to keep their eyes on that larger prize of societal change as they watch the Chauvin trial unfold.

“Lawyers can only do so much,” he said. “We as a society need to keep pushing to improve the system. Otherwise, there will be another King or another Floyd, just with another name.”

Follow USA TODAY national correspondents Deborah Barfield Berry @dberrygannett, Javonte Anderson @javontea and Marco della Cava @marcodellacava

Source: Read Full Article