Indian airlines brave Covid turbulence

Though India’s airlines are certainly bleeding, they haven’t yet faced the ignominy of shutting down.

Sai Manish reports.

India’s biggest domestic airline, Indigo, commanding half the domestic aviation market share, recently posted its fifth consecutive quarterly loss of over Rs 1,100 crore (Rs 11 billion).

One of the fastest-growing pre-pandemic airlines, Spicejet has completely eroded its net worth.

The Wadia family-backed GoAir (rechristened Go First) has hit the market to raise funds to sustain the airline.

Tata-backed Vistara has deep pockets to dig into if the dire forecasts for 2020-2021 continue.

The rebirth of Jet Airways under new owners is still being talked of in hushed voices.

Air India’s privatisation has taken multiple hits due to the pandemic. The past year hasn’t been good news for India’s aviation.

Yet this was one of the world’s most promising markets till 2020.

From government support for connecting small towns and remote islands to promoters willing to buy more planes to expand fleets, to newer international players interested in stakes in airlines and airports to India’s domestic airlines soaring ambitions to venture into long-haul flying — the last few years have been great for Indian aviation.

The pandemic has turned the clock back.

Though India’s airlines are certainly bleeding they haven’t yet faced the ignominy of shutting down or going into bankruptcy protection like UK’s Flybe and Virgin Atlantic, Chile’s LATAM, Air Mauritius and AeroMexico among others.

So how is India placed in the bloodbath the pandemic has unleashed on global aviation?

While India forms just two per cent of the global domestic aviation market, its airlines have been estimated to have taken a $4 billion hit in 2020 alone owing to declining ridership due to various travelling restrictions (chart 1).

This is a fraction of the $119-billion hit airlines expect to suffer globally, the loss is still significant considering the precarious finances of various airlines.

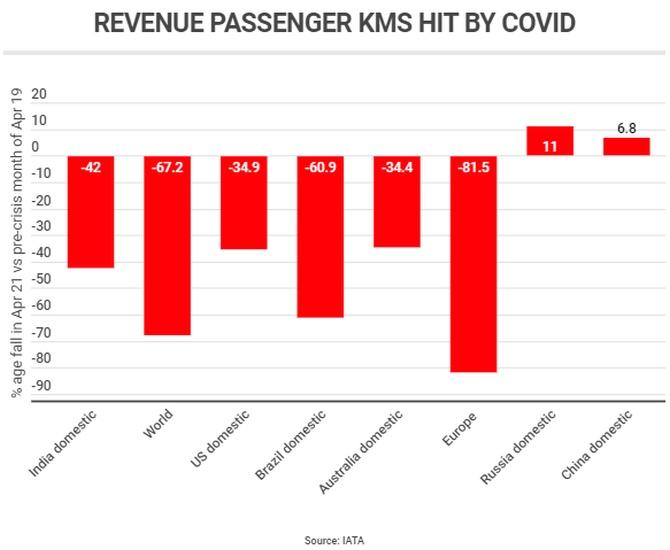

One of the crucial metrics for any airline is its revenue passenger kilometres (RPKs), a true measurement of airline traffic.

Chart 2 shows how much India’s airline traffic (or RPKs) fell in April 2021 over the pre-crisis levels in April 2019. Only Europe and Brazil fare worse.

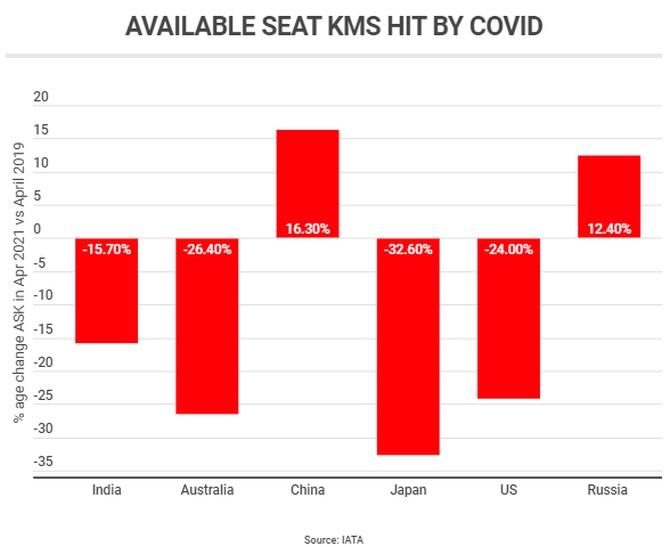

Another crucial metric that has a bearing on airlines revenues are available seat kilometres (ASKs), which indicate the number of seat kilometres available for purchase on any airline.

A corresponding decline in the distance travelled by an aircraft and the number of seats bought on the aircraft shows the decline in the money earned from a particular flight.

Chart 3 shows India figures behind the third worst performer among major aviation markets.

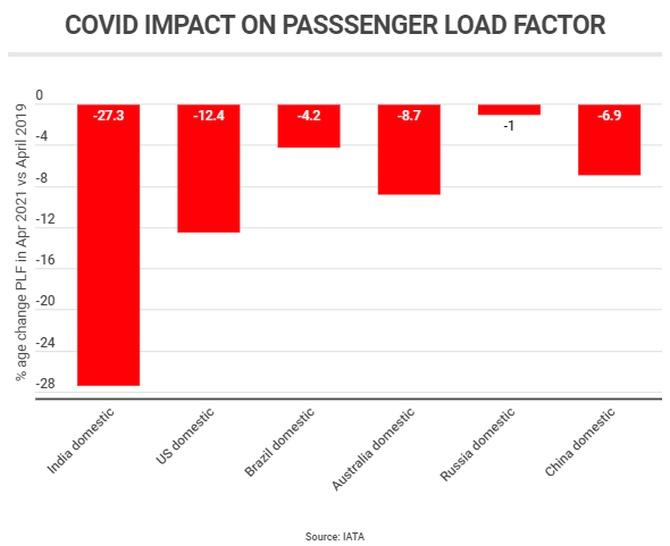

Even as India and other nations unlocked, a bevy of restrictions and general reluctance to travel on planes meant that most airlines were operating below capacity.

This is borne out by the steep decline in passenger load factors, which indicate occupancy rates on any given flight (chart 4). India is by far the worst performer on this metric.

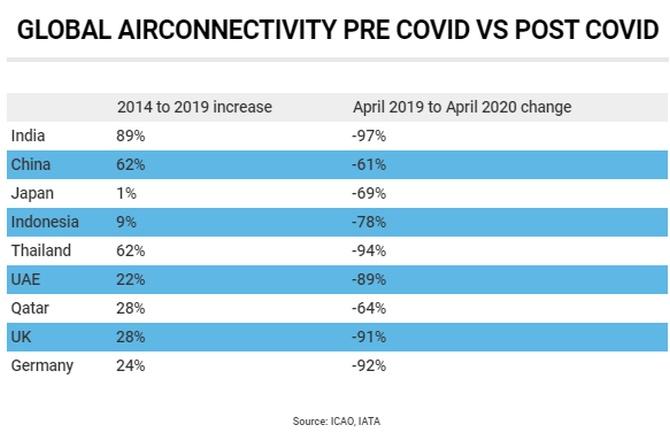

Domestic flying was banned for a couple of months in 2020 in India, and the pandemic also forced many nations across the world to shut their airspace and borders.

This led to a dramatic fall in cities within a country and globally that were connected to each other.

As chart 5 shows, India, which was one of the most aggressive nations connecting its own small towns in addition to connecting more cities to global destinations between 2014 and 2019, saw one of the biggest impacts of Covid-induced restrictions.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article