Not a Budget for Employment

It is important to increase employment in general.

It is even better to increase good quality jobs.

Strategically, it is important to move people from farms to factories to improve overall labour productivity.

It is important to improve job opportunities for women, for urbanites and for the educated.

The Budget does not contain ideas to do any of this, points out Mahesh Vyas.

The Government of India does not recognise any employment problem in the country.

Two important statements it made related to the economic situation in the country over the last four days — the Economic Survey and the finance minister’s speech — did not recognise, in any manner, the fact that scores of millions of Indians lost livelihoods in 2020-2021.

Most people found ways to reduce their misery with or without help from the government.

The government does not recognise this phenomenon and therefore it does not directly address it in the two documents released by it recently.

The finance minister’s speech contained no specific scheme to help the unemployed or to generate employment directly.

Hopes of an urban version of MGNREGA were belied.

The finance minister did not mention MGNREGA in her speech.

The scheme was a major saviour of employment in rural India during the lockdown.

Budgetary allocation for the scheme was raised from Rs 615 billion to Rs 1,015 billion because of the lockdown and the need to provide employment.

The revised estimate is raised further to Rs 1.115 billion.

The budgetary allocation for the scheme in 2021-22 is Rs 730 billion.

A scheme to promote textiles proposed by the finance minister could generate employment.

The government proposes to set up seven Mega Investments Textiles Parks over three years.

Textiles is the largest manufacturing sector employer in India.

Even if this scheme is successful, it is unlikely to move the needle on employment much.

Similarly, the higher allocation for roads or housing is unlikely to make a material difference to employment.

The challenges on the employment front are much bigger.

Budget documents presented in Parliament tell us that central government employment would be 3.41 million in 2020-21.

This implies a 3.4 per cent growth in central government employment over the 3.31 million it employed in 2019-2020.

But last year’s Budget documents of the government had told us that employment in 2019-2020 would be 3.62 million.

So, the government has revised its employment estimate of 2019-2020 down by about 310,000.

Interestingly, last year, they said that the employment in 2018-19 was 3.49 million.

But now they tell us that employment then was 220,000 lesser at 3.27 million.

So, the employment in 2020-2021 at 3.41 million would be lower than what they said the employment was three years earlier in 2018-2019 at 3.49 million.

This is if the estimate for 2020-2021 is not revised downwards.

Historical data tell us that central government employment has been stable at about 3.3 million since at least 2000-2001 when it was at this level.

The average employment in the 19 years, from 2000-2001 through 2018-2019, has been 3.26 million in a year.

Central government employment maxed at 3.42 million in 2001-2002 and was at its lowest of 3.15 million in 2011-2012.

The last five ‘final’ estimates of 2012-2013 through 2018-2019 show a steadily declining trend of central government employment.

Given this historical record, the projection of employment of 3.4 million in 2020-2021 and 3.3 million in 2019-2010 seem like tall claims.

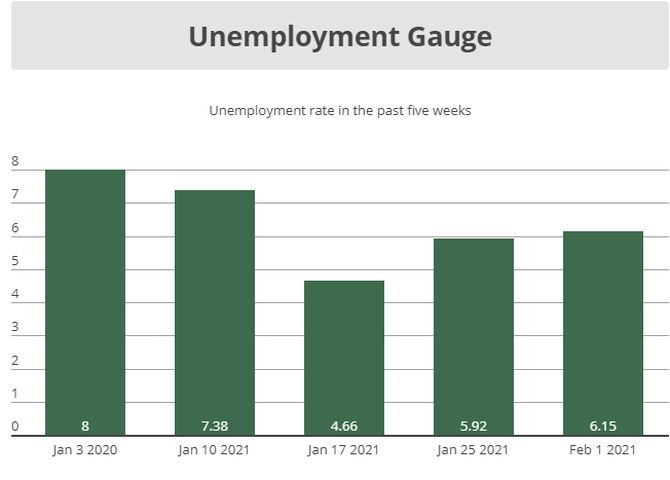

Meanwhile, labour markets recovered in January 2021 from the setback they suffered in December 2020.

Employment increased by 11.9 million in January to reach 400.7 million.

This is the first time since the lockdown that employment crossed the 400 million mark.

The increase in employment in January is concentrated in the construction and in agriculture sectors.

Employment in construction increased by 8.6 million — from 62.1 million in December 2020 to 70.7 million in January 2021.

The growth in employment in agriculture was relatively modest at 4.2 million.

It increased from 144.9 million to 149.1 million over the same period.

The manufacturing sector saw a marginal improvement in employment from 29.3 million to 29.7 million.

Services industries saw a fall in employment during this period.

Some of these monthly changes reflect seasonality and also the monthly changes in the sample.

Because of the highly disruptive nature of economic growth in recent years for a variety of reasons, deciphering the seasonal components of growth is not possible.

A year-on-year comparison helps overcome both problems.

Because of the panel nature of the CMIE’s Consumer Pyramids Household Survey, the sample of January 2020 is the same as it was in January 2019.

Compared to a year ago, employment in January 2020 was lower by 9.8 million.

The sector-wise breakup shows that the employment grew in agriculture and it fell in industry and services.

It grew in agriculture by 10.6 million but it fell by 14.3 million in manufacturing and by 10.1 million in services.

It is important to increase employment in general.

It is even better to increase good quality jobs.

Strategically, it is important to move people from farms to factories to improve overall labour productivity.

It is important to improve job opportunities for women, for urbanites and for the educated.

The Budget does not contain ideas to do any of this.

Mahesh Vyas is MD and CEO, CMIE P Ltd.

Source: Read Full Article