Richard Prebble: Thinking the unthinkable – the return of stagflation

OPINION:

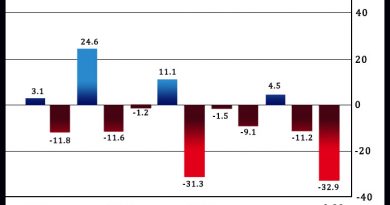

The Reserve Bank said last month that “annual consumer price inflation is expected to peak around 7 per cent in the first half of 2022”.

Governor Adrian Orr has also told the International Monetary Fund that curbing inflation will require “more targeted effective fiscal policies”.

Finance Minister Grant Robertson immediately rejected the advice. Robertson confirmed that this month’s Budget will provide record government spending at a time of full employment.

Combating inflationary government spending requires very strong monetary policy.

Inflation is a monetary phenomenon: too much money chasing too few goods. Printing a billion dollars a week for over a year was always going to be inflationary.

Inflation is also psychological. When we expect prices to increase, they will increase. Consumers’ expectations of inflation accelerated during the latest Roy Morgan/ANZ Bank survey. The BusinessNZ survey revealed that most businesses intend to increase their prices.

The Reserve Bank said in April that it increased interest rates “to head off rising inflation expectations”. That horse has already bolted.

Wage rises are a cost that businesses must pass on. Once wages are increasing to compensate for inflation, then the wage-price cycle is established.

The wage rise horse is off and running. The Federated Farmers-Rabobank April survey shows agricultural workers’ pay over the last two years has increased by 13 per cent. Dairy managers’ salaries jumped 25 per cent.

My Rotorua “out-laws” have quit their jobs and gone kiwifruit picking. Pickers are earning up to $60 an hour. To attract them back, their previous employer will have to increase wages significantly.

The Reserve Bank admits that “employment is above its maximum sustainable level”. The bank also notes the opening of borders will increase labour shortages as more Kiwis leave than arrive.

The wage-price cycle is underway, and inflation is being entrenched in the economy.

Domestic inflation is over the bank’s official target of 3 per cent.

Where is the strong monetary policy needed to curb inflation?

In April, the bank said “the OCR is stimulatory at its current level”.

With the CPI at 6.9 per cent and the official cash rate at just 1.5 per cent, real interest rates are negative.

Bank economists are predicting the OCR will reach 3.5 per cent sometime next year. It is not high enough to curb an inflation rate of over 7 per cent. Commentators believe the bank will never raise interest rates high enough to halt inflation because the economic distress will be too great.

The bank will use its “path of least regret” approach and its twin target of maximum sustainable employment to avoid taking effective action against inflation.

With record government spending and loose monetary settings, why should inflation peak within the next two months? The bank is relying on external factors.

Those external factors include supply chain disruptions ending, oil prices falling and a return to China being a major disinflationary force. None of these things will happen in the next 60 days.

A fifth of the world’s container ships are at anchor awaiting a berth. Oil prices will fluctuate but the war in Ukraine will keep gas and oil prices elevated. Covid is disrupting China’s manufacturing.

While these factors may improve, those things will never be as cheap as they were.

Shipping companies have retired ships to start to decarbonise the global supply chain. The new ships take time to build and are expensive.

“Just-in-time” has become “just-in-case”. There is a worldwide shortage of warehousing to hold the just-in-case freight. The supply chain is permanently more costly.

Oil was increasing in price even before the Ukraine war. Investors are reluctant to fund exploration in a sunset industry. Cheap oil is never going to return.

For 30 years, China’s ability to produce everything from T-shirts to TVs at cheaper and cheaper prices has been a significant disinflationary force. But demographics means China’s workforce is reducing. China’s labour costs are rising. Switching to lower cost Asian countries is only a partial solution.

Then there are the global economic shocks. The war in Ukraine is increasing the global price of food.

It is wishful thinking for the Reserve Bank to rely on overseas events to return New Zealand to low inflation. The political parties are no better.

Labour thinks it can mitigate inflation with tax and spend. National thinks it can curb inflation with tax cuts and trimming government spending.

Only strong monetary policy can give New Zealand low inflation.

Inflation matters. Inflation ruins the middle class. The median wage was $58,836 as of June last year. Inflation at 6.9 per cent means the average worker is robbed of $4059.68 a year.

It gets worse.

Economist Ludwig von Mises warned: “There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion”.

Labour’s policies are spend, tax and bust.

Just because double-digit stagflation is unthinkable does not mean it will not happen.

Richard Prebble is a former leader of the Act Party and former member of the Labour Party.

Source: Read Full Article

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/OWPHBOGDASRQGI2HO6ZTASISSQ.jpg)