Monopoly Money: Framing Bitcoin as the last-mover in blockchain

This post originally appeared on Medium, and we republished with permission from its author Jack Davies.

Competition is for losers. At least that’s the thesis given by Peter Thiel in a particularly eye-opening guest lecture he gave at Stanford University a few years ago. In a little over forty minutes, Thiel paints the landscape of modern industry and commerce as one with a striking dichotomy at is heart: the opposing forces of competition and monopoly.

When most of us think about business in the 21st century, there is a tendency to conjure a scenario of fierce competition in our minds. Enterprises that live and die by the sword of the global markets, in a fervent and ceaseless struggle to win the hard-earned cash of the man on the street. Each new startup enters the fray of battle for a slice of the global economy, battling fiercely to gain market share in increasingly congested sectors, jockeying for a sustainable position amongst a sea of competitors. At least, this is the mental image I usually create when pondering the global marketplace today.

Thiel, on the other hand, offers a reframing of this understanding. Instead, the chief goal of companies, now more than ever, is not to merely compete with its peers, but to blow them out of the water entirely. He argues that the truly successful businesses of the World today are those that are able to create so much value, and capture so much profit, that they gain a ‘last mover advantage’ in their domain.

These are companies akin to Apple, Google, and Tesla, which have brought such significant paradigm-shifts that they have changed the very nature of their sectors. There is a reason that the word ‘Google’ has entered our global vocabulary as a replacement for any and all synonyms for ‘search’. These are the monopolies of the world and this, Thiel argues, is the name of the game.

[…] you want to be the last mover, you want to be the last company in a category. Those are the ones that are really valuable.

Whether this is a good thing for global trade, and wider society for that matter, is an open question and one that is receiving increased scrutiny as every day passes. It is undeniable that even the most monopolistic of companies provide consumers with immense value, but the salient question is: at what cost? Most of us will use numerous Google products many times each day for free, as an essential part of daily life. But in the background, our data is harvested by opaque algorithms and sold to the highest bidder. This is a complex issue in and of itself, and not one I seek to resolve here, but it is important to bear in mind nonetheless.

Instead, I want to explore how the principles of monopoly articulated by Thiel may apply to a very different system: Bitcoin.

Foundations of a monopoly

On my first watching of Thiel’s lecture, I was almost immediately struck by the key characteristics he ascribes to monopolies. This was partly due to the insights themselves, which I had not previously understood as the hallmarks of monopoly, yet instantly resonated with common sense and intuition. But more profoundly still, I was taken aback at the keen similarity between the nature of the monopolies he discusses and the properties of Bitcoin itself.

In a superficial sense, this is something that I had already considered to be true to a degree. Bitcoin is by far the best-known, and most widely discussed example of peer-to-peer cash the world has seen. In fact, it was the first system that solved the famous ‘double-spending’ problem, which had plagued the pursuit of digital cash for decades, and in effect gave birth to an entire industry whose total market cap now stands at an impressive $500bn. Bitcoin has historically dominated this market given that is was the first mover, and it is no great leap to think of Bitcoin as having so far, in practice, monopolised the wider industry that it started.

Nevertheless, Thiel’s description of monopolies in the business domain provides a far stronger framework for understanding how Bitcoin operates like one itself. We can use these concepts to see exactly how Bitcoin has achieved its current status as the de facto king of its industry, and extrapolate into the future to see how Bitcoin is likely to further consolidate its power and dominance in the blockchain world as time progresses. Needless to say, its origins give Bitcoin a good shot at becoming the last mover, too.

The first trait that Thiel associates with monopoly is that they tend to begin in smaller markets, only expanding into larger and tangential domains as they begin to grow and capture larger value share in the initial sector. A great example is Facebook, which entered the nascent realm of social media in 2004, but has since grown its sphere of influence in acquiring over 80 companies and even branching out into physical products like Portal recently.

When we look at the blockchain industry through this lens, we can see that Bitcoin, too, follows this philosophy. The original white paper, released in 2008 by Satoshi Nakamoto, had a clear target: the payments sector. Pitched by Nakamoto as an electronic cash system to allow for the “possibility for small casual transactions” to occur over the Internet, Bitcoin began its life as a disruptor in payment-processing. This may at first sound counter-intuitive, given that the market for digital payments is enormous. Dominated by the likes of PayPal, VISA, and Stripe, the sector is estimated to be worth well over $70bn by 2026, which doesn’t exactly seem like a drop in the ocean.

But, when you consider the size of the much larger market that Bitcoin is evolving to address, it begins to seem like a humble starting point. The market I am alluding to is data.

Even a cursory glance at the blockchain industry will tell you that data is the new hot ticket, and many big-players and high-ranking decision-makers are starting to converge on solving issues related to data as the primary value proposition.

The problems around data are myriad, and well-documented at this point. Everything from privacy vulnerabilities of online services to the growing unrest with the lack of robust data-ownership for the users of online platforms are captured under this umbrella. So, too, is the analytical revolution being undertaken in Artificial Intelligence, where the procurement of vast, high-quality data sets is a primary concern. Even our more traditional industries, such as fishing, raw-material harvesting, and manufacturing, are acknowledging the transformative power of the blockchain to improve trust and transparency in global supply chain.

Crucially, these are all problems that Bitcoin, and the immutable nature of its data, are poised to address. This, then, means that the total addressable market Bitcoin is lining up is far greater than just that of digital payments, and it is growing into these additional domains as the system itself increases in size, volume, and notoriety.

Another defining aspect of successful monopolies is their ability to leverage the startling power of network effects. These effects enable businesses to grow rapidly by reaching a critical mass of usage, awareness, and dependency that their products start to become ubiquitous all on their own.

Some examples of these would include applications like TikTok and Instagram, which inherently amplify network effects by the nature of their design, as well as SaaS companies. These examples also betray another hallmark of modern monopolies; namely that they are built around products with extremely low marginal costs. This property allows a product to be replicated to a high volume of customers at very little cost to the business itself. Having low marginal costs allows network effects to take hold uninhibited by scale, so long as the capacity of the business to provide their service or product can outpace the incoming demand.

However, a caveat that Thiel is right to emphasise is that these effects are most effective due to the effect of compounding over time, and this means they can be difficult to get going in the first place.

Returning to Bitcoin, once again we can draw a few interesting comparisons and find similarities. It, too, has benefitted thus far from network effects related to its price and usage, which create cyclical demand and frenzy around the asset itself that is amplified by mainstream media attention. The total market cap of BTC has peaked as high as $650bn in recent months, approaching the scale of some of the public companies that are typically synonymous with monopoly. The impact of network effects is clear in explaining how Bitcoin has reached this status. However, we can also look at how these network effects were instigated by considering the design of the system itself.

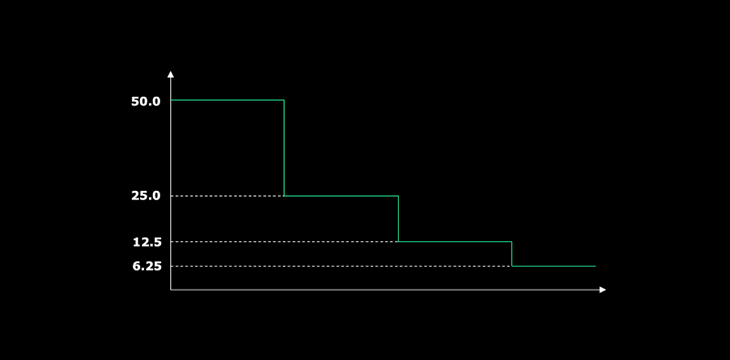

Satoshi recognised that the Bitcoin network would need to be bootstrapped if it were to survive, and we can see this in the distribution schedule of its native tokens.

The supply of Bitcoin, totalling just under 21 million tokens, is a pre-destined parameter of Bitcoin, and is distributed over time to miners on the network who successfully produce blocks. The rate at which the tokens are distributed halves on an (approx.) four year cycle, starting out at 50 Bitcoins per block, and abating periodically. At the time of writing, the rate has already fallen to just 6.25 Bitcoins per block.

The key word missing in this description so far is subsidy. This process of distributing tokens to competing miners can be viewed in economic terms as an industry subsidy that has the effect of bootstrapping the entire ecosystem.

Arguably, without this subsidy mechanism in place, the incentive to mine on the network until this point would have been non-existent, and none of the network effects that are now in play could have ever come to fruition. We can see, then, that perhaps Satoshi was a particularly long-term thinker, putting in place one of the final pieces of the puzzle that could facilitate the growth of the Bitcoin network into a world-dominating monopoly for digital cash.

And what about marginal costs? Well, for this we need to understand what exactly the ‘product’ is in Bitcoin. As I’ve already mentioned, the benefit Bitcoin brings to the end user is efficiency in payments and reduced costs for transacting on the Internet. The cost of replicating this benefit for many users is in fact incredibly low, given that anybody using Bitcoin simply needs to set up a wallet and broadcast their own transactions, which has become much simpler in recent years through a multitude of applications and services.

This leads us nicely on to the final primary characterisation of monopolies that Thiel highlights. Bitcoin is able to target these large markets and start to leverage these network effects largely because of its technical merit.

You want to have a technology that is an order of magnitude better than the next best thing.

The observation that most monopolistic companies spawn from technological innovation is useful in its own right. If we look to history, we find examples of this dating back to the industrial revolution, such as the Carnegie Steel Co., which gained its status partly due to technical innovations and increased efficiency in the production of steel. In more recent memory, the advances made by Google with algorithms such as PageRank enabled the company to emerge from the early stages of the Internet as the standard for modern information search and retrieval. Barring cases where organisations operate outside of the law, wherever we find monopolies in business we also tend to find technological progress at the centre.

But innovation alone is not the sole driving force that forges these types of super-organisation. As Thiel points out, the technology advancements that accompany such businesses tend to be paradigm-shifts in their fields. These are either completely new solutions to well-known problems, which enable people to do something that was previously impossible, or they are an improvement over an existing technology that provides dramatically better user-experience, lower-cost, or improved efficiency. In each case, these improvements need to be orders of magnitude better than the closest competing technology that achieves the same goal.

Take Amazon, for example, which was able to design processes and systems using technology that allowed them to reduce costs so much that they are able to sell 10x as many books as their nearest competitor. Only when advances of this gravity are made do we see monopolies formed.

It’s clear that this is also a trait that Bitcoin embodies strongly. The key breakthrough made by Nakamoto was to find a robust solution to the double-spending problem associated with digital cash. Otherwise known as the ‘Byzantine Generals Problem’, the issue of enabling secure peer-to-peer value transfer in the absence of a trusted third party was unsolved prior to the advent of Bitcoin.

However, this is only one side of coin when considering how Bitcoin resembles a monopoly through technological advancement. In fact, it is quite reasonable to argue that Bitcoin both cracked this previously unsolved problem, and did so in such a way that it could facilitate payments at a fraction of the cost of existing systems. By removing third party intermediaries from online transactions, Satoshi’s triumph was in drastically reducing the cost of making these types of payments. No longer was it necessary to pay a large fee to send money to a recipient across the globe using PayPal or Western Union. Instead, Bitcoin presented an alternative where a much smaller fee can be offered to a network that compete to earn it, rather than acting as rent-collectors for payment systems.

The key thing to note is that the median cost of a Bitcoin transaction can be on the order of hundreds or thousandths of a cent using its design. This represents a huge cost saving when compared with the incumbents, which often have fixed minimum fees 100–1,000 times this figure. The reduction in the cost of transacting online is therefore (one of) the key areas in which Bitcoin’s technological advancements present the kind of paradigm-shifting improvement that bears resemblance to a monopoly.

Intrinsic and extrinsic monopoly

So far, we’ve been using Thiel’s framework for describing monopolies to help show how Bitcoin has the key characteristics required to emulate one. But what does it actually mean to classify Bitcoin as a monopoly?

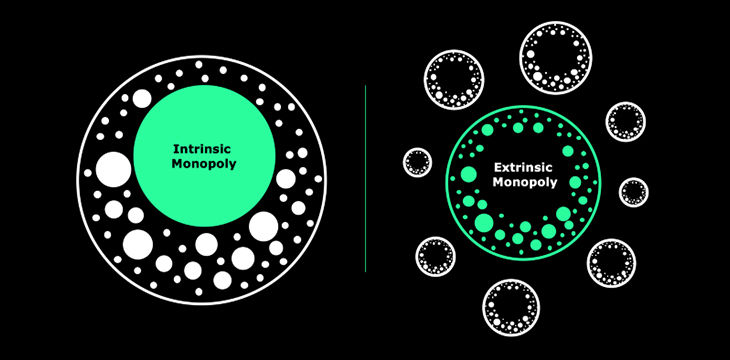

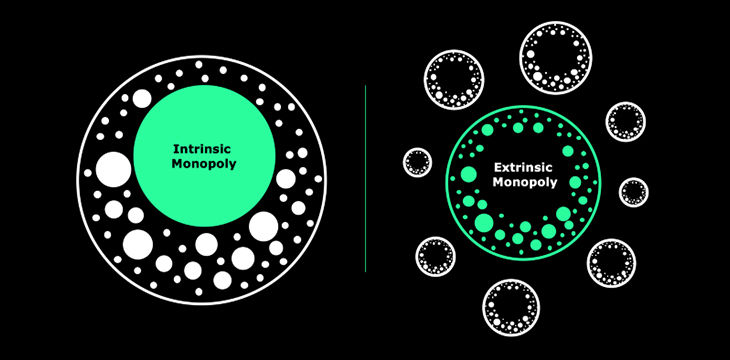

One glaring omission in my argument so far is that the term itself typically refers to a single business entity. Bitcoin, on the other hand, is a system underpinned by a network of agents, each of which may be its own company and have its own corporate existence. To make the leap from labelling singular businesses as monopolies to doing the same for Bitcoin, I’d like to coin a pair of new terms that apply to business networks like Bitcoin.

Intrinsic monopoly: this refers to the monopoly of a single business entity (e.g. a single miner) within a network like Bitcoin.

Extrinsic monopoly: this refers to the monopoly of Bitcoin itself with respect to competing Bitcoin-like systems (e.g. other blockchains).

These new terms can be used to complete the picture we’ve laid out so far. The design and properties of Bitcoin as a system form the foundations for it to attain the status of an extrinsic monopoly. That is to say that a feasible end-state for Bitcoin is that it emerges as the dominant blockchain in terms of all pertinent metrics, including transaction volume, market capitalisation, and total daily value transfer. To use Thiel’s framework once again, we may expect that Bitcoin becomes the last mover in the blockchain industry, in addition to having been the first.

Why is this a reasonable end-game for Bitcoin? Looking to the history of the Internet can help provide us with an answer.

After the initial development of the Internet’s core infrastructure, one of the most well-studied market bubbles—the “dot com” bubble—was formed in a culture of increased speculation on disruptive technology. The problem was not that the underlying technology that kicked-off the market cycle was inherently flawed; indeed it still underpins the same Internet that you are using to read this article now.

No, the real problem came when the superficial aspects of the technology became prevalent in the marketing of companies only tangentially-related to the real innovations that forged the Internet. The bubble came about because the market tried to mimic the appearance of the open, public Internet in other companies and their private, permissioned systems. When the market later realised that only the original Internet design could provide the benefits touted by its imitators, the bubble popped and the world re-aligned itself around a single, universal public Internet.

You may have already guessed that this sequence of events has a striking resemblance to the growth of the blockchain sector. At the time of writing, there are just shy of 4,000 digital assets and tokens listed on the market, many making similar claims that resemble the original promises of Bitcoin. It is likely that we are seeing a similar cycle play out to that which caused the dot com bubble at the turn of the millennium.

If the ‘crypto’ markets also make an analogous correction in the future, then we might ask which system will emerge from the ashes? Whichever blockchain does so will have effectively achieved an extrinsic monopoly for itself. Based on the framework Thiel provides, I would argue that Bitcoin is likely the best candidate to play this role given that, as a system, it has all the key traits of a monopoly.

There is only one global chain.

— Satoshi Nakamoto

This sentiment is echoed by Bitcoin’s creator, too, who has made the case on several occasions that the true end-game for Bitcoin is to become a viable payments system for the entire planet.

Value-capture by utility

At this point, you would be forgiven for wondering whether any blockchain would survive such a market capitulation. When assets are wildly mis-priced, and the market swiftly corrects them, we tend to see those prices revert to levels set by the fundamentals of the assets. These fundamentals can be easy to measure in the case of traditional stocks and assets; public companies provide data that can be used for more ‘objective’ valuations of their shares, while physical asset classes such as gold or platinum can be valued based on their tangible properties and their associated supply and demand.

But where does these leave Bitcoin, or the thousands of other blockchain tokens on the market? For the most part, these are non-physical assets whose valuation is determined entirely by ‘market-forces’, albeit in a nascent and teething marketplace. In the aftermath of a widespread market-correction, or simply in the wake of longer-term glacial changes in the sector, what can be used as a ‘fundamental’ for setting the price of these assets?

While this may yet be up for debate, I think a reasonable guess as to Bitcoin’s price-setting fundamental in the future will be its utility. By this, I mean to say that the aggregate value that Bitcoin can provide to its entire set of users may become a natural lodestone for its price. Finding the price of the individual tokens of Bitcoin becomes simple if we can quantify the overall value-capture of the system itself.

This value-capture can also take many forms in Bitcoin: it can come from enabling low-fee transactions, or granular micropayments, while it can also be sourced from supply-chains or even entire governments using Bitcoin as an immutable data ledger to improve trust and transparency in modern systems. The through-line here is that the overall value of Bitcoin can be derived from its utility, and it is this characteristic that may come to define its eventual value-capture as a monopoly.

It is important to caveat that much of these potential sources of utility for Bitcoin users is yet to be realised in practice. At present, these are all capabilities of the blockchain, but they have not yet been adopted widely enough to account for the value of a Bitcoin that has achieved a fully-fledged extrinsic monopoly. However, this speaks to another trait of monopoly that Thiel describes.

Most of the value of these companies exists far in the future.

Indeed, this quality of monopolies is a reinforcement of the idea that to be the last-mover in an industry is the ultimate goal. When a company can position itself as the last player in the game then it can reap the rewards of that status for a technological dynasty.

The same is true of Bitcoin; if it can succeed in gaining extrinsic monopoly status, then the vast majority of the value that the network can capture may lie in the future. This is particularly apt given that the markets Bitcoin is targeting, including both global digital payments and the data infrastructure of both the Internet and global supply chains, are projected to continue growing further still.

A most competitive network

The final aspect to consider about Bitcoin’s monopolistic nature is the possibility of an intrinsic monopoly. Recalling the definition we gave this term earlier, for Bitcoin to have an intrinsic monopoly would mean a single miner were able to outcompete all other miners by an order of magnitude.

The first thing to note about this scenario, is that it would imply a single miner has control of well over 50% of the network. This makes the situation highly unlikely, particularly if the Bitcoin system itself has already achieved an extrinsic monopoly. In other words, if the Bitcoin network has achieved the level of scale and value-capture to make it the last-mover in blockchain, then it would become vanishingly unlikely that any single business entity would be able to achieve an intrinsic monopoly within the network at the same time.

Nonetheless, let us suspend disbelief and imagine for a moment that it were feasible for a miner to achieve such an intrinsic monopoly. The economic incentive model underpinning Bitcoin is competitive by design, meaning that the system encourages the cooperative competition of multiple miners in the network to build and publish blocks. A key aspect of this mechanism is that the users of Bitcoin gain confidence in the system based on this fact: that miners compete with one another to confirm users’ transactions, rather than acting as a trusted third party to do so.

The confidence of users that Bitcoin works in this manner contributes to their perceived utility of the system, which, as we have already discussed is intimately related to its total value-capture and token price.

If a miner attempts to achieve an intrinsic monopoly within Bitcoin, then by definition the competitive aspect of block-production ceases to apply. For this reason, a miner attempting to create an intrinsic monopoly would quickly undermine the overall utility of the network for its many users, which would in turn impact the price of the Bitcoin tokens they are attempting to earn. This has the result of disincentivising the creation of an intrinsic monopoly.

In fact, we might go as far as to say that Bitcoin is intrinsically competitive, which mitigates the risk of an intrinsic monopoly forming. This interpretation becomes clearer if we think of Bitcoin acting as its own economy. Within the system, there is room for innovation and competition; each Bitcoin miner acts as an individual business in the economy that can provide specialised services to customers of the network. The difference between Bitcoin and any existing economy, is that intrinsic monopolisation is less profitable than competition.

As a final thought, perhaps Bitcoin exemplifies the power of both monopoly and competition. It may be able to establish a monopoly on digital cash and data-management systems in the years to come, but it may only achieve this by harnessing the competitive nature of its core design.

Watch Peter Thiel’s guest lecture, “Competition is For Losers,” at Stanford University:

Source: Read Full Article