Exhaust emerges from the smokestack of a natural gas-fired power plant in Berlin, Germany.

(CNN)Imagine a world entirely free of fossil fuels. That’s no longer such an abstract concept, as most of the everyday things we do can be powered by electricity — driving a car, heating a home, charging a phone or computer — and all that energy could come from sources like the wind, the sun and the natural movement of water.

For industries that need more oomph than solar or wind can offer — like aviation, steel and concrete — there’s hydrogen. And it’s everywhere.

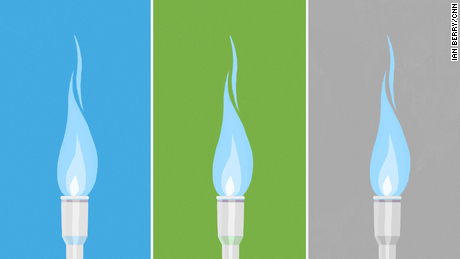

There’s a lot of buzz and billions of dollars being poured into the hydrogen industry, but not all types of hydrogen are created equal. Hydrogen is the most abundant element on the planet, but it needs to be isolated from its source, and that in itself takes energy. At the moment, it’s mostly derived from fossil fuels — natural gas, coal and oil — in what’s called “gray” hydrogen. If the carbon-dioxide (CO2) emitted during production is captured, you get “blue” hydrogen.

As governments around the world devise new energy strategies to rapidly remove the carbon from their economies, major fossil fuel companies are lobbying hard to keep blue hydrogen in the mix. In doing so, energy and climate experts say, they are locking in the global use of natural gas, a planet-warming fossil fuel, potentially for decades to come.

The most promising hydrogen for the climate is really the “green” sort, which is derived from water and is processed using 100% renewable energy, making it a potential zero-emissions power source. Green hydrogen is seen as a game-changing solution to emissions in the heaviest of industries, but it has a long way to go — less than 1% of the world’s hydrogen today is green, according to Fitch Ratings. The rest comes from fossil fuels.

An analysis provided to CNN from the independent climate think tank InfluenceMap, which uses data to track the influence of business and finance on climate policy, found that several major fossil fuel companies are using the hydrogen hype to keep natural gas on the playing field, and that’s having an impact on a crucial upcoming decision in the European Union.

The EU’s 27 countries are so divided on the future role of natural gas that the bloc’s executive arm, the European Commission, has for months failed to deliver what should be a simple list of energy sources that it considers sustainable.

After several delays, the decision was again postponed on this week, as countries squabbled over whether gas — as well as nuclear power — should make the list, and whether they should be called “green” or “transitional” forms of energy.

Earlier draft versions of the list — known as the Sustainable Finance Taxonomy — made no mention of gas or nuclear, a source close to the talks told CNN, and now EU officials are publicly saying they will almost certainly be included. That could allow natural gas operations to carry on with a green stamp of approval and unleash a wave of private investment and green recovery public funds to new projects.

In an opinion piece for the website Euractiv, Greta Thunberg and follow climate activists described the list as “fake climate action.”

Using a database of more than 350 of the world’s largest companies, InfluenceMap identified a number of major fossil fuel companies that have been active in lobbying the EU on the sustainable fuels decision, as well as two other policies on gas and hydrogen. The three most active companies were Equinor, TotalEnergies and BP, the analysis concludes.

Gas industry associations representing some of the biggest fossil fuel companies operating in Europe are also arguing that natural gas in new projects could be blended with hydrogen — including blue hydrogen — to make it “cleaner.” Vivek Parekh, an InfluenceMap analyst, described this lobbying to CNN as a “slow creep” of natural gas back into EU energy policy.

“The positions put out initially by the European Commission looked to push fossil gas infrastructure down the back road, and try to avoid it as much as possible,” Parekh said.

“But it looks like the gas industry — after such a long fight — has managed to weaken the sustainability criteria in its favor. And that essentially secures the role of fossil gas and its long-term energy future. This is in the European Union, which is supposed to be a policy leader when it comes to climate.”

The EU has one of the most ambitious climate plans in the world, with a goal enshrined in law to reduce emissions by 55% by 2030, from levels in 1990. Its policies tends to influence those in other parts of the world, making this decision particularly consequential.

Pascal Canfin, the EU lawmaker who chairs the bloc’s powerful environment committee, said he was hopeful of a compromise to break the impasse. One proposal put forward, Canfin told CNN, is to include gas but impose a limit to how much carbon dioxide (CO2) new projects should be allowed to emit. Another could be to only allow new gas projects when they replace coal, and a “sunset clause” ending any new gas infrastructure as of December 31, 2030.

“So here are three key conditions under which you can define your design, the space where gas can be considered as useful for the transition, even if it’s fossil,” he said.

Equinor and TotalEnergies were among companies that campaigned against the proposed CO2 limit, according to InfluenceMap.

Equinor — which is investing in green hydrogen but also continues to drill for more oil and gas — confirmed to CNN it had been engaging with the EU on the policy and said it would support the CO2 limit in electricity and heat projects, but that it would not in other circumstances, for example, new gas projects to help a region transition from coal.

“Like many member state governments we see natural gas as key to the EU’s decarbonization efforts,” the company said in a statement to CNN. It emphasized that natural gas can be “decarbonized” through carbon capture and storage.

But no technology that exists today can remove 100% of the CO2 from natural gas, and a landmark study on blue hydrogen from Cornell University in August showed that blue hydrogen, at the moment, emits 20% more than natural gas in the first place. That’s partly because the greenhouse gas methane tends to leak in the carbon capture process.

French company TotalEnergies did not comment on its position on the emissions limit, but said it was investing in both blue and green hydrogen. It argued natural gas is currently “the best option for providing the world with the energy it needs while combating global warming,” and is even “a champion of energy transition.”

BP did not reply to CNN’s request for comment.

A growing gas addiction

Despite its clean-sounding name, natural gas is a major contributor to the climate crisis. It is made mostly of methane, a greenhouse gas more than 80 times more potent than carbon-dioxide in the short term. It surged in use in the ’70s and took off in the ’90s, when it was sold as a “bridge fuel” — a cleaner alternative to coal and one that would eventually be dropped when renewable energy took off.

But the world has become somewhat addicted to gas, and that “bridge” has become so long, governments are realizing they don’t really know when and where it ends.

Global use of natural gas is at an all-time high, according to the International Energy Agency. In the EU, it’s come down slightly since a 2010 peak, but not that much, and is still higher than levels in the ’90s.

The scale of growth in the EU is a clear sign that, even in Europe, gas isn’t going anywhere soon.

Data from Global Energy Monitor (GEM) shows that at the end of 2020, there were around 17,000 kilometres (around 1,500 miles) of gas pipeline in development in the EU. That’s 65 projects across 23 nations worth 72.6 billion euros ($81.8 billion). There were another 15.5 billion euros-worth of projects for liquified natural gas.

And, depending on how they are built, new natural gas projects tend to stick around for some time.

Greig Aitken, who manages GEM’s Europe Gas Tracker, said that pipelines and the gas plants they serve typically have lifetimes of 30 to 40 years, warning that any new gas infrastructure will either lock in the fossil fuel and undermine the bloc’s climate goals or force the projects to be abandoned.

“A tipping point has been reached, and there really should be no new commissioning of gas infrastructure from now given the timelines involved, unless companies and their financial backers actually welcome the idea of having stranded assets on their books,” Aitken said.

So where does that leave green hydrogen? The industry needs a windfall in funding to build more electrolyzers — the machines needed to extract hydrogen from water — as well as a huge increase in renewable energy sources.

A decision like the EU’s on taxonomy could potentially mean money that could be going to green hydrogen is diverted to blue.

But there is huge momentum. A new green hydrogen project appears to pop up somewhere in the world on a weekly basis, and even fossil fuel companies promoting blue hydrogen are beginning to look at green as well. The International Renewable Energy Agency says that green hydrogen could become cheaper than blue hydrogen by 2030 if — and it’s a big if — the industry gets enough buy-in.

“Green hydrogen proves that the world has a clean, practical, implementable way out of global warming,” said Andrew Forrest, whose company Fortescue Future Industries is investing heavily in green hydrogen.

Forrest, an Australian who made his fortune from mining with the Fortescue Metals Group, is betting big on green hydrogen to not only decarbonize his company’s entire mining operation, but also to transform Fortescue into a global renewables giant.

To Forrest, all this talk about blending blue hydrogen into natural gas is a distraction. The energy transformation has to happen now, and not lock in yet another “bridge” fuel, he said.

“Fossil fuel companies trying to tell the world that natural gas, blue hydrogen or gray hydrogen are a solution to climate change are lying,” Forrest said.

“Blue hydrogen, gray hydrogen, any type of hydrogen that is not green is dirty and uses fossil fuels to make it. It is like clean coal or cancer-free tobacco.”

Source: Read Full Article