It’s a $50b-a-year export industry. How long until coal’s rivers of gold run dry?

By Nick Toscano and Mike Foley

Credit:

If the end of coal is near, it’s hard to see it among the open pits and billowing cooling towers of Victoria’s Latrobe Valley and the Hunter in NSW.

Canyons of brown and black coal, set between green paddocks and sloping hills, loom large in these mining districts and dominate their economies as a source of great wealth, just as they have for a century or more.

A global push is accelerating to eliminate the use of thermal coal — the worst-emitting source of energy — to restrain the planet’s rising temperature and avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change.

But the mines in Latrobe and the Hunter are still operating around the clock. White steam still rises from the nearby power plants as they burn coal to supply more than two-thirds of Australia’s electricity needs. And, at the ports, huge volumes of coal are still being loaded onto cargo ships bound for Asia, bringing in billions of dollars of export revenue a year.

Peter Jordan, the president of the northern mining and NSW energy division of the CFMEUCredit:James Brickwood

“The coal industry is just so damn important to the regional centres,” says Peter Jordan, a Cessnock local and mining union official who worked in the sector for more than a decade.

“Our coal mining jobs are well-paid relative to other industries, but they support many others in the mining communities; services, retail, health … most of them wouldn’t exist without coal.”

With 50,000 coal mining jobs nationally, the industry’s head count is relatively modest in contrast to sectors such as manufacturing, which employs 900,000 Australians. But coal has an outsized influence in a handful of seats, where it is a provider of good jobs and rich revenue streams for governments.

“It sends rivers of gold to Sydney in the form of royalties,” Jordan adds, “paying for roads, schools, and hospitals.”

For now, coal is a $50-billion-a-year export industry. How long until its rivers of gold run dry?

This question, and others about the future of coal, drive some of the deepest divisions in modern Australia.

Former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull lost his job over an attempt to reshape energy policy and push down emissions. Scott Morrison went to the last election warning voters that Labor’s “net-zero” target would unleash economic havoc and widespread lay-offs. Most Australians now say they want stronger emissions curbs, new polling suggests. But fewer than half (49 per cent) think coal power should be phased out within a decade and 44 per cent want to keep mining and exporting coal for as long as buyers want it.

Australia’s coal addiction might seem hard to shake. While 10 coal-fired power plants have shut down in the past decade, coal still generates about 70 per cent of the nation’s electricity.

Winds of change are, however, blowing anyway. The clean energy era is firmly upon us. And powerful forces are radically reshaping coal’s outlook overseas and on the home front.

With 3.3 gigawatts of new wind and solar power capacity plugged into the nation’s main grid in 2020 alone, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) has officially declared the transition to be the fastest of anywhere in the world, describing the pace as “absolutely staggering”.

A consequence of more wind and solar farms being built, and more Australians installing rooftop solar panels, is that coal is getting squeezed. In the past 12 months, the flood of cheaper-to-run renewable energy has pummelled daytime wholesale power prices to levels where just about every coal-fired power plant is considered at risk.

This year, EnergyAustralia brought forward the closure of its Yallourn power station to 2028, four years ahead of schedule. Last week, it said it would shut its Mt Piper plant earlier, too, sometime prior to 2040.

Other sites, though, are still licensed to be burning coal until the back half of the 2040s, or even the 2050s, putting Australia at odds with a growing chorus of world leaders calling for a markedly more urgent phase-out plan.

Ahead of the world climate summit in Glasgow, the United Nations has launched a push for all OECD countries to quit coal power by 2030, and non-OECD countries by 2040.

“The alarm bells are deafening,” UN secretary-general Antonio Gutteres says.

Is it possible for Australia’s coal-dominated national power market to be rid of coal entirely by 2030?

“It depends,” says Lisa Zembrodt of Schneider Electric, an adviser to many of Australia’s largest corporate energy consumers.

As the rapid rise of clean energy pummels coal’s profitability, Victoria’s Yallourn power station is closing four years early.Credit:Joe Armao

Put this question to the power station operators, and they invariably insist 2030 is far too soon and would raise the threat of a “messy” transition that could see price volatility or even blackouts.

AGL, which accounts for 8 per cent of Australia’s total emissions, says nine years is not nearly enough time for replacement capacity to be invested in, built and plugged into the grid.

“We certainly recognise that the date of 2030 is something that is on the table with respect of the UN targets,” AGL chairman Peter Botten says. “I believe that 2030 is a very, very challenging target.”

Still, at its annual investor meeting last Wednesday, more than 50 per cent of AGL’s shareholders including US investment powerhouses BlackRock and Vanguard defied the board and voted to support an activist climate resolution requesting consideration of new goals that would compel accelerated coal plant closures.

What it boils down to, according to Zembrodt, is a choice we have to make as a society: As expensive as it may be, are we prepared to invest in the transition — smart grids, micro-grids, demand-management technology, batteries, energy storage and infrastructure — to fill the gap?

“We should be seeking to phase out coal as quickly as possible … and 2030 is a great aim,” she says. “But we need clear policy, we need market design, we need coordinated efforts between government, the market operators and consumers to enable the transition and support it, rather than prevent it.”

Grattan Institute energy director Tony Wood agrees: Australia could be capable of retiring all its coal plants and replacing them with clean energy by 2030, but it would cost a “huge amount”.

“You would have to do a hell of a lot of things in the shorter-term that you otherwise would only have done in the longer term,” he says.

Because electricity production is a dominant source of emissions, exiting coal would help sharply reduce the country’s carbon footprint. At the same time, however, state and federal ministers have also become acutely aware to the risk of abrupt plant closures leading to undesirable outcomes for consumers.

Federal Energy Minister Angus Taylor is driving development of a so-called “capacity mechanism” designed to spur investment into “dispatchable” assets – those capable of supplying on-demand power when the wind isn’t blowing and sun isn’t shining.

Taylor insists the mechanism would be technology-neutral, with equal opportunity for gas, pumped hydro and batteries. But the policy has drawn fierce criticism from environmental advocates who have dubbed it “CoalKeeper” because it may see coal plants paid to guarantee future supply by remaining in the grid for longer.

The heated debate about the fate of the coal sector and campaigning by green groups for the fossil fuel’s demise have traditionally prompted a defensive response from those employed in the industry, says Tony Wolfe, 58, a Latrobe Valley power plant worker.

Tony Wolfe, 58, works as a unit controller at a Latrobe Valley coal-fired power generator.Credit:Jason South

In more recent years, he says, the mood has begun to shift towards an acceptance of the future: while coal provides an essential service today, its end is on the horizon.

“We will still need electricity, and coal will be part of the mix for the next 10 years minimum, I would say … but it will be a diminishing part and, as coal communities, we need to accept that.”

What power workers need is “certainty” about the development of future industries in their regions, which Wolfe says are ripe for investment in large-scale renewable projects due to existing infrastructure and connectivity to the grid.

“The new jobs that are going to be created with the new technology probably won’t be as well-paid and definitely won’t be as many … but surely any jobs are better than none if you let that sort of industry escape to other areas.”

Mine workers, too, are under no illusion on the outlook. “People understand it’s inevitable … but they’ll tell you it’s going to be a massive threat to the community,” Jordan says. “Governments should invest in new industries like manufacturing that will create good, better-paid, blue-collar jobs, but we should absolutely continue to support our coal mines and this industry in the meantime.

“Our coal is a great export, so why not continue to export it?”

BHP mines thermal coal at Mt Arthur in NSW.Credit:Janie Barrett

In the town of Muswellbrook, in NSW’S Upper Hunter, BHP’s Mt Arthur coal mine has been a feature of the economy since the 1960s. The global-scale open-cut sends about 17 million tonnes a year to the export market and, a few years ago, had a $2 billion value on the company’s books. This year, faced with looming rehabilitation requirements, it’s now listed as $275 million liability. BHP is trying to sell Mt Arthur – its last thermal coal asset – and has been looking for a buyer. It has found none willing to pay the right price.

NSW thermal coal has rallied this year to $US180 a tonne – a 10-year-high, and a sign of enduring near-term demand despite accelerating emissions goals globally. Yet BHP’s Mt Arthur predicament tells much about the longer-term problems plaguing the sector.

As economies re-emerge from COVID-19 and energy consumption rebounds, coal markets are booming. What will happen next, though, is decidedly less certain. Top Australian coal destinations – Japan, China, South Korea – are targeting “net-zero” emissions by 2050-60, which, eventually, will diminish demand for fossil fuel cargoes.

There is much still to be answered. How sharp will the trajectory in those countries be? Will the world seek to limit global temperatures to 2.5 degrees of warming, 2 degrees or the most aspirational 1.5-degree pathway, as targeted by the Paris Agreement? What does that mean for Australian coal?

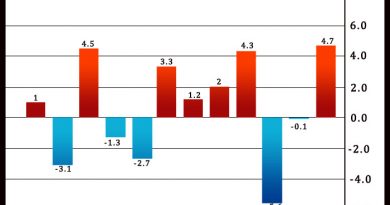

When the Reserve Bank of Australia considered these questions, it modelled four scenarios. Under one scenario of no change to existing policies in those countries, Australian coal exports rise 17 per cent by 2050. In other scenarios in which temperature rises are kept at 2 degrees or lower, coal falls by up to 80 per cent by mid-century.

“Countries are unlikely to materially alter their energy mix in the near term, and … demand for coal will likely remain robust this decade, the RBA said. “However, as global appetite for coal tapers off from 2030 onwards under all scenarios except for the baseline, Australian coal-related investments are at risk of becoming ‘stranded assets’.”

Elsewhere in Asia, beyond Australia’s mainstay export markets, the outlook is equally uncertain, says energy economist Simon Nicholas.

”The opportunity for export growth into these markets is rapidly falling away,” says Nicholas, a specialist in Asian markets at the Institute for the pro-renewables Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “Plans for coal-fired power plants are being slashed right across south-east Asia.“

Coal producers and analysts say Australian coal – with a relatively high quality and energy content – could face a brighter future than coal from other sources, as countries across Asia retire their older, less-efficient coal generators and move towards lower-emissions facilities.

If Asian demand remains stronger for longer, Australia’s ability to develop new mines is not a sure thing. Major banks, insurers and investors are abandoning the sector in droves on ethical and financial grounds, pushing the cost of capital for coal companies ever higher.

“The move is on”, says Emma Herd, Ernst & Young’s climate change and sustainability partner. Will the Australian government opt to follow the flow or swim “against the tide”?

“If everybody else goes down, we could end up holding a bigger piece of the global coal pie,” says Herd. “But is that who we really want to be? Do we want to be the last coal exporting-nation in the world?”

Most Viewed in Business

Source: Read Full Article