I’m Still Blasian and Proud, Even When It Feels Like the US Hates Both Sides of Me

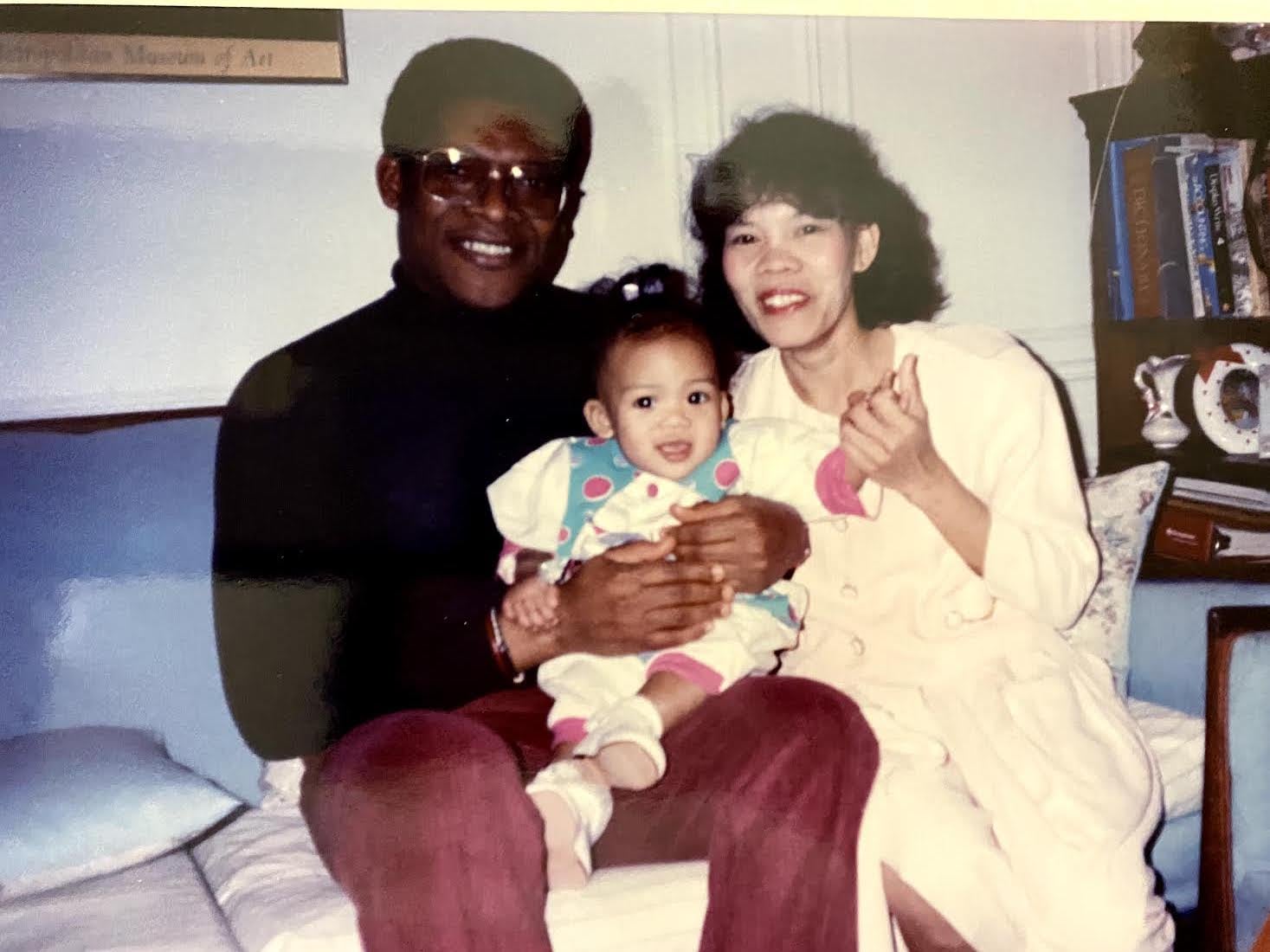

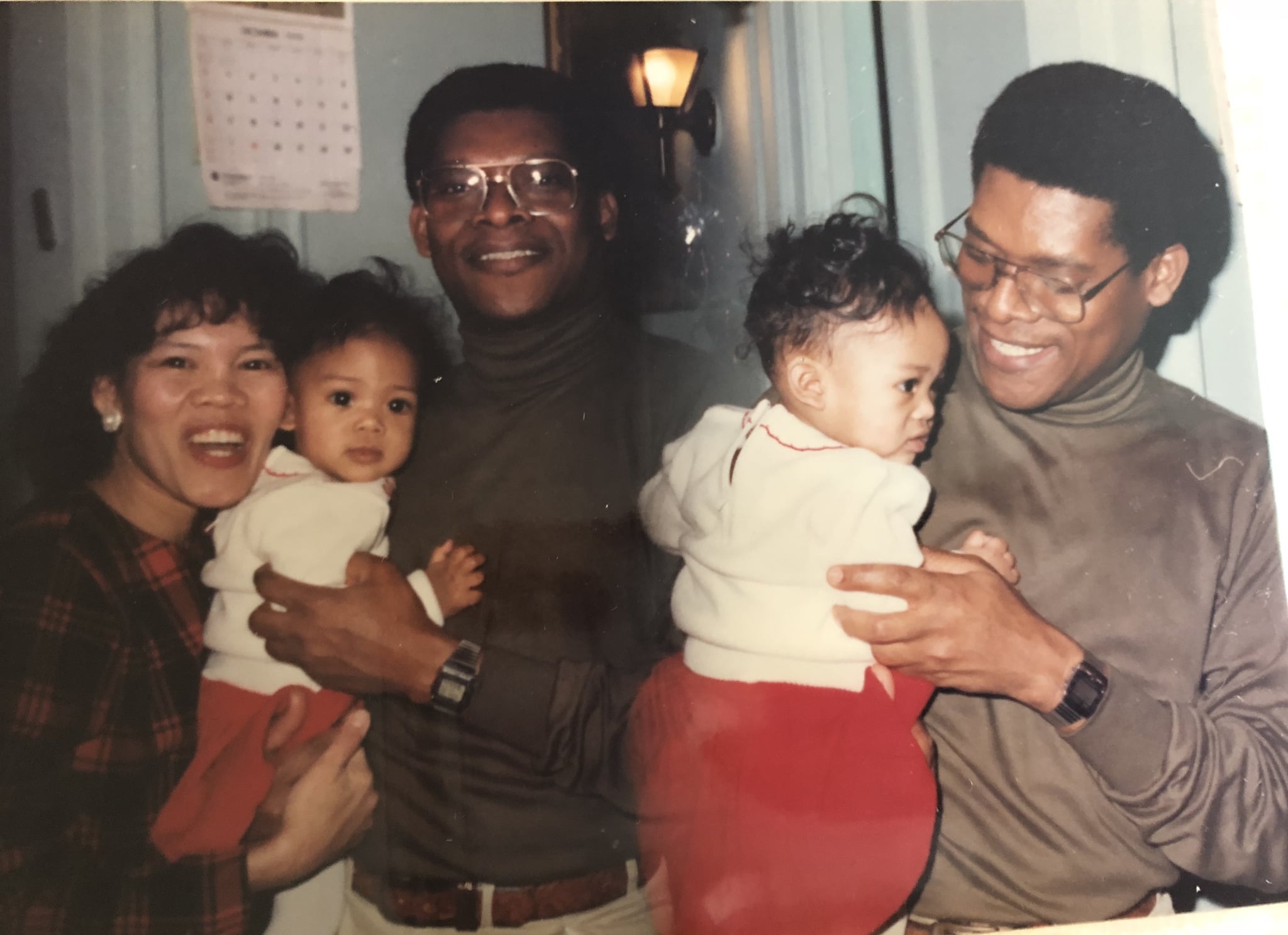

Growing up biracial, I spent most of my childhood feeling like I didn’t fit in. I was always told I look too Black to be considered Asian, or that I’d never really be accepted as Black because I’m mixed. Despite the hurtful comments, I’ve always considered myself part of the Filipino and Ghanaian diasporas and identified as both. I never felt the need to choose between either of my cultures because they’re inseparable from who I am.

Having a strong sense of self keeps me buoyant, but I’ve been struggling to stay afloat since eight people – six of whom were of Asian descent – were killed in three Atlanta-area spa shootings on March 18. The hesitation to call the shootings a hate crime is infuriating, but what has bothered me most is seeing the negative response to the Stop Asian Hate and Black Lives Matter movements.

Being Blasian in America’s current racial climate means walking around with a target on my back. Cops could shoot me dead in my home, like they did Breonna Taylor and Deborah Danner, or I could be attacked while protesting anti-Asian violence. It means having to be twice as good at my job or excel as a “model minority” only to get a fraction of the recognition and pay as my white co-workers. Republican lawmakers want to suppress Black voters like me and defend the use of racist language like “kung flu.”

The recent attacks against both groups has reignited tensions between Black and Asian people in America. Social media has erupted into another round of Oppression Olympics, with some folks trying to prove that their race has endured more discrimination than the other. Meanwhile, I’m the designated referee on the sidelines trying to mediate the misunderstanding.

I understand why some Black people are apprehensive about uplifting a group whose members have co-opted and commodified their culture while often telling their children not to bring home a Black significant other. I also can see why some Asians are wary of accepting support from Black people when some rappers use anti-Asian slurs in their music and highly publicized instances of anti-Asian violence sometimes involve a Black assailant. But focusing on our perceived differences distracts from our common enemy in the fight for racial equality: white supremacy.

The United States has a history of scapegoating both Black and Asian people. Black people were enslaved in America for nearly two and a half centuries before the practice was abolished in 1865. The US government banned Chinese immigrants from becoming US citizens through the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. From 1942 to 1945, Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps, and despite Filipinos sacrificing their lives in the American Civil War, they were denied a chance at citizenship until 1946. Today, Black and Asian Americans are among the thousands of victims of police-involved deaths in the US.

Learning the history of my people and taking pride in my cultures are crucial in helping to strengthen solidarity between the Black and Asian communities. Knowledge is power in the era of fake news, and although Facebook has been criticized for spreading misinformation (looking at you 2016 and 2020 presidential elections), I still consider it a valuable learning tool for people who are willing to venture outside of their echo chamber. The platform has allowed me to educate other Asians on how to own up to and unlearn anti-Blackness and help some Black people recognize that racism isn’t monolithic.

Black-Asian unity has been a thing since the 19th century, when abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells spoke out on behalf of Filipinos when they fought the US for their freedom during the Philippine-American war. Chinese-American activist Grace Lee Boggs spent 70 years of her hundred on Earth fighting for racial justice in Detroit. To help combat the myth of Black and Asian division, I share my experiences and relevant information whenever I can, to whoever is willing to listen.

Although I worry about the safety of my friends and family, I’ll never allow fear to stop me from being Blasian and proud. Seeing messages of Black and Asian solidarity from so many social justice organizations makes me hopeful that someday no child will ever feel othered or be told by the country they were born in that their life doesn’t matter. As the fight for racial equity continues, a Maya Angelou quote powers me through: “You may write me down in history with your bitter, twisted lines. You may trod me in the very dirt, but still, like dust, I’ll rise.”

Source: Read Full Article