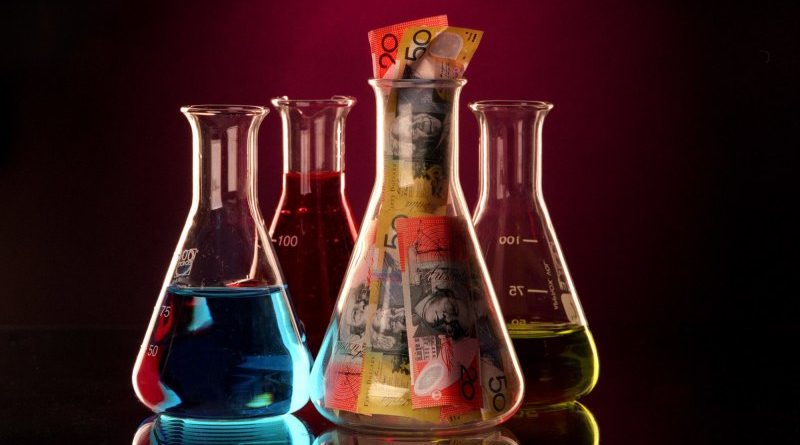

How money can corrupt science – and what to do about it

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Examine, a free weekly newsletter covering science with a sceptical, evidence-based eye, is sent every Tuesday. You’re reading an excerpt – sign up to get the whole newsletter in your inbox.

When we bought our small apartment, I was delighted to assume ownership of a Bosch gas rangehood.

I like to cook. And, my mum had long assured me, there was no better way to cook than with gas. The extreme, quick heat. The control.

For years many of us believed gas was best for cooking, without any thought of the risks involved.Credit: John Woudstra

It never crossed my mind that I was, essentially, burning a fossil fuel right in my face and filling my apartment with the fumes. I saw only the benefits and none of the risks.

Why? Why would I (and my mum) believe gas was best?

Possibly because of a subtle but highly effective campaign by the gas industry to manipulate both science and public opinion.

In the US at least, the industry successfully muddied the waters about the risks of gas while successfully making us think that gas means good cooking, a new report suggests.

Gas is not alone. Industries including tobacco, food and chemicals play the same game – even deploying copycat strategies – say a group of researchers. In the US, declining rates of government investment in science mean that business is now its major funder; business is also a major science funder in Australia.

“A lot of evidence, across chemicals, tobacco, food, energy, pharmaceuticals, suggests when corporations fund science, the results of that science are questionable – because they are more likely to favour the sponsor,” Ray Moynihan, an assistant professor at Bond University who has published a book on the topic, tells me.

“The common thread here is we need, as a society, to be much more sceptical about industry-funded science.”

New concerns about the health effects of gas seem to have emerged from thin air (pardon the pun) in the past few years.

But an investigation by American non-profit media outlet NPR, published this month, revealed US government scientists in the 1970s found that exposure to nitrogen dioxide – a byproduct of gas cooking – increased the risk of respiratory diseases.

The American gas industry responded the same way the tobacco industry did when challenged over the safety of its products: it funded big tobacco’s preferred scientists to generate studies that muddied the waters on the risks posed by gas stoves.

“People don’t realise tobacco is one of many industries that have done the same thing – they have been aware of the dangers of their product, and they’ve been intentionally undermining or suppressing the harmfulness of their products,” Dr Nicholas Chartres, a University of Sydney researcher who studies the way companies work to thwart regulation of dangerous products, told me. “They have intentionally muddied the waters around how strong the science is.”

Chartres has organised a conference on so-called commercial determinants of health, a nice way of describing industry influence, in Sydney next week. His team has a roll-call of bad corporate actors, many of whom you might not suspect.

Tobacco companies deliberately used high levels of nicotine, and added menthol and sugars, to make their cigarettes as addictive as possible.

But more surprising to me is the allegation from researchers that the same tactics have been used in so-called “ultra-processed foods”. These industrially produced foods, often containing things we don’t normally eat such as high-fructose corn syrup and maltodextrin, have been implicated in the obesity epidemic.

The foods are manufactured, in many cases, by companies that were at one point owned by tobacco companies.

Those companies used big tobacco’s strategies, incorporating caffeine, sugar and salt in ways that “excessively activate brain reward neurocircuitry and facilitate excess caloric intake,” argues a paper published in Addiction earlier this year.

Indeed, the steepest increase in highly processed foods sold in America came between 1988 and 2001, when tobacco companies owned major food companies; the paper finds food produced by brands owned by tobacco companies were dramatically more likely to qualify as highly processed.

A PFAS plant in Cottage Grove, Minnesota. It was one of the main manufacturing plants for forever chemicals that have contaminated the world.Credit: Bloomberg

The story is similar for PFAS chemicals, widely used as insulators, flame suppressors and in non-stick cookware. Publicly, the chemicals were considered biologically inactive until around the year 2000. But privately the chemical industry had conducted several studies linking them to health effects in animals.

As reported by my colleague Carrie Fellner earlier this month, instead of warning the public, the manufacturers withheld the science, funded favourable studies and ran communications campaigns claiming the chemicals were safe.

Says Chartres: “There was a two-to-three decade lag between when they knew and when it first got publicly reported. And we now know 98 per cent of the US water supply is contaminated.”

The tobacco industry has not been idle either. When Australia banned tobacco advertising, the industry sponsored Formula 1 racing, which had an exemption as an international event.

When smoking rates were squeezed down to 11 per cent in Australia, the industry introduced vapes, which capture an ever-increasing slice of the youth market.

“You need to find a loophole – and then you blow it out so it becomes a window you can waltz right through,” says Associate Professor Becky Freeman, a University of Sydney researcher who specialises in tobacco control.

What are the solutions? Chartres has perhaps the most novel: a ban on commercial money in science.

We know industry funding bends results. Why allow it at all? Perhaps, suggests Chartres, we could allow industry to fund studies through a blind trust administered by the government.

“Until we have that mechanism,” he says, “we’re never going to have research that is free of this empirical bias.”

Liam Mannix’s Examine newsletter explains and analyses science with a rigorous focus on the evidence. Sign up to get it each week.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article