Is the real scandal that so much of our pensions were at risk?

A £1.5 trillion death spiral: Is the real scandal that reckless financiers were able to risk so much of our pensions, asks GUY ADAMS

- So-called liability-driven investment strategies (LDIs) use collateral to raise cash

- The strategy leaves funds highly sensitive to sudden moves in the price of bonds

- Collapse of LDIs would have threatened pension schemes of ten million people

One day in May 2019, a Dutch financier named Hans Van Zwol hit ‘send’ on a document outlining what he suggested was a ‘terrible’ threat to the global economy.

It was several months before Covid would up-end money markets – and the Ukraine war, which would later turbo-charge our cost of living crisis, was but a figment of Vladimir Putin’s imagination.

Van Zwol was, therefore, sounding the alarm about something entirely different. Namely, the bespectacled fund manager had become concerned about a range of complex products known in the trade as ‘Leveraged Liability-Driven Investments’ or LDIs.

Though virtually unknown outside the unglamorous world of pensions, these obscure financial instruments were by then being used to manage quite extraordinary amounts of cash.

In the UK, where they had barely existed 15 years earlier, LDIs were then representing around £1trillion in assets held by ordinary people’s pension funds. Today that figure has risen to a massive £1.5trillion, which equates to two-thirds of our country’s entire gross domestic product.

Leveraged Liability-Driven Investments were responsible for the chaos that paralysed bond markets for a short time on Wednesday morning, forcing the Bank to make an emergency intervention

On paper, these huge investments are supposed to be low-risk. That was how such bonus-soaked finance houses as Schroders, Legal & General and BlackRock – ex-employer of former chancellor George Osborne – were supposed to have designed them, at least. Yet Van Zwol took a subtly different view.

In a research note published by his employer, the asset-management firm NN Investment Partners, he explained that while LDIs could indeed be ‘useful’ when ‘incorporated prudently’ into a pension fund’s portfolio, they could also cause ‘instability’ if fund managers instead decided to use them too aggressively.

Especially, he went on, should interest rates suddenly rise.

‘Interest rates may be low at the moment,’ wrote Van Zwol. ‘But the risk of rates rising in future is real…Our research shows that even a small rate increase can have a dramatic impact… In addition, there is always the risk of a crisis that would lead to an increasingly volatile interest-rate environment.’

At the time, Van Zwol was something of a lone voice and his stark warning was roundly ignored.

Indeed, one might fairly describe the somewhat dry research note (headline ‘Leverage in LDI: A wonderful servant, a terrible master’) as having sunk without trace. Yet today his words seem remarkably prescient.

Indeed one might go so far as to describe the cerebral 60-something – who hails from Ridderkerk, near Rotterdam – as a sort of canary in the coalmine who somehow managed to foresee the crisis that descended on the City of London this week, causing what the Bank of England dubbed ‘a material risk to UK financial stability’. That is because LDIs were responsible for the chaos that paralysed bond markets for a short time on Wednesday morning, forcing the Bank to make an emergency intervention. The ‘Old Lady of Threadneedle Street’ was bounced into announcing it could purchase £65billion in Government debt to prevent first the pension system and then the entire British economy from suddenly unravelling.

The ‘Old Lady of Threadneedle Street’ was bounced into announcing it could purchase £65billion in Government debt to prevent first the pension system and then the entire British economy from suddenly unravelling

To understand how this came to pass, under the nose of regulators who are supposed to protect consumers and markets from serious risk, we must wind the clock back to the early 2000s – when company pension funds began coming under scrutiny over their ability to finance generous final-salary payouts.

Created in an era when most workers died a few years after retirement, many pension schemes by then boasted insufficient funds to meet their obligations to members who were expected to live well into their 70s or 80s. At one point, more than four in five were officially classified as under-funded.

LDIs were designed to solve this problem by using the tens of millions of pounds which most pension funds already held in low-risk Government bonds – or ‘gilts’ – as collateral to raise extra cash. This could then be funnelled into a package of other investments. Typically these other investments would include yet more gilts, along with a smaller proportion of corporate bonds, shares, commodities and property.

The big idea was that the extra package of investments would then grow over time, helping the pension fund become better placed to meet its obligations. As ever in the investment industry, the Masters of the Universe who created these products were paid a percentage of cash under management. It was no small amount – the value of LDIs in the UK was an astonishing £500billion by 2012 and it has tripled over the ensuing decade.

For years, the system worked relatively well. Indeed, in the ten years to January, while stocks recovered from the financial crisis, the proportion of pension schemes which were under-funded fell from 80 per cent to around 20 per cent.

During the Covid crisis in 2020, the yield of gilts (then regarded as a ‘safe haven’) fell to almost zero, meaning that their value rose substantially. This in turn meant that pension funds were required to hold less cash as collateral for the bonds they kept in LDIs, allowing more money to be returned to their pot.

The genius of these products was that, despite performing solidly, they looked extremely conservative – at least on paper. Government bonds are among the most reliable investments. The world of pensions is designed to be dull. While the sheer volume of gilts being packaged into these products was unprecedented, regulators and the vast majority of observers saw nothing in the way of red flags.

Yet, as ever in the world of investing, greater rewards tend to carry greater risk. And with pension funds becoming more and more comfortable using LDIs to dramatically ‘leverage’ their holdings – at times using them to purchase £3 of gilts for every £1 they actually invested – they would inevitably become sensitive to changes in market conditions.

For a few short hours, early on Wednesday, the market became effectively paralysed. That forced the Bank of England to take dramatic action

Specifically, as Van Zwol predicted back in 2019, LDIs were vulnerable to rising interest rates because such changes inevitably lead to a commensurate rise in bond yields. That in turn reduces the value of gilts held by pension funds, which then leave those funds needing to raise extra capital to cover existing obligations.

In the early months of the year, that is exactly what came to pass. In a bid to combat inflation – which became especially critical following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – central banks began slowly and surely ratcheting up interest rates from their historically low levels.

While the pace of change was initially gradual, meaning pension funds could cover their positions, the change began to spook some industry experts, including Calum Mackenzie, a partner at AON investments. In June he published a research note warning that the ‘seemingly sedate’ world of bonds and LDIs was being ‘rocked by the sort of rises in yields that we’ve not seen for decades.’

Mackenzie urged pension funds to ‘dramatically reduce their risks’. A colleague from the consultancy Mercer at the same time reckoned that leverage ratios were ‘moving towards critical levels’. Not long afterwards, Mackenzie pointed out that some LDIs had already fallen even further than the benighted crypto-currency Bitcoin and were poised to drop still more.

Yet neither the industry nor regulators seemed to act. Indeed, as recently as July, an article by a writer in the Financial Times noted that: ‘LDI managers claim that their activities pose no systemic risk and I read the Bank of England financial policy committee’s silence as agreement.’

Events of recent days would, of course, prove them (and the Government) quite wrong. Negligent, even. Trouble began on Monday of last week when Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng unveiled a colossally expensive energy price cap, limiting the total amount that households and businesses will pay on their bills.

That caused investors to lose confidence in the Government’s ability to service its debts, meaning that the interest rates it was forced to pay on gilts ticked upwards. On the Thursday the market was again spooked when the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee chose to increase the base rate by 0.5 per cent – significantly lower than the 0.75 per cent that the Federal Reserve in America had recently plumped for. This had the effect of making UK gilts less attractive.

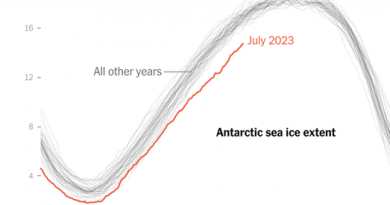

Finally on the Friday the Chancellor’s ‘mini-Budget’, containing tens of billions in further uncosted tax cuts, led to more of the same. By early this week, gilts which had been worth £3.50 in January were valued at as little as 50p.

For pension funds which held LDIs, this caused immediate problems. The UK gilts they were using as collateral on other investments were suddenly worth an awful lot less and cash was needed to plug the gap. Unfortunately, the only way they could raise cash was to sell large quantities of gilts, which in turn had the effect of driving the price even lower.

Of course, that meant they needed even more loot. And so a sort of vicious circle was created. ‘I have called it the death spiral,’ Mackenzie said last night. ‘That’s what we were in. A sort of volatility vortex. It became self-fulfilling. Pension funds were essentially eating themselves.’

For a few short hours, early on Wednesday, the market became effectively paralysed. That forced the Bank of England to take dramatic action, stepping in as a sort of ‘buyer of last resort’ and agreeing to plough about £65billion into gilts over the coming weeks.

As the dust settles, and taxpayers count the cost, there will naturally be calls for a prompt investigation into how pension funds were allowed to invest billions in such high-risk products. Smooth financiers, who for years profited from these exotic deals, will shrug their shoulders while politicians deflect and regulators seek others to blame.

History, meanwhile, suggests no one will be properly held accountable. And therein lies the real scandal. For as so often when financial markets implode, the outrageous fact is that this was well and truly a crisis foretold.

Source: Read Full Article