‘Even the RBI was caught by surprise and was totally unprepared to handle its fallout’

I kept insisting that Rs 100 notes were in short supply and there was an urgent need to augment the supply of 100 rupee notes while also rapidly bringing into circulation the proposed new Rs 500 notes.

But this was easier said than done because all the note printing machines of the RBI were programmed for printing Rs 2,000 notes and required at least three weeks before the machines could print the new Rs 500 currency notes.

The availability of currency paper posed another major bottleneck, and it had to be imported.

It was only when the supply of the new Rs 500 notes started improving and the process of change of cassettes at the ATMs gathered momentum that the situation began limping back to normal.

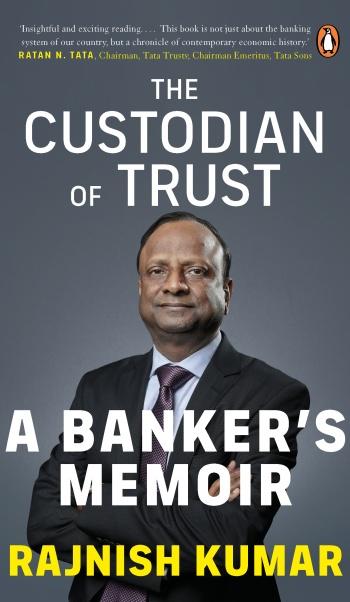

A fascinating excerpt from former SBI chairman Rajnish Kumar’s The Custodian of Trust: A Banker’s Memoir, five years after demonetisation, November 8.

Even as the banking system was still fighting the war on NPLs (non performing loans, two other major events occurred that I had to handle as the Managing Director, Retail Banking.

One was the merger of the five Associate Banks and Bharatiya Mahila Bank with the SBI, and the second — an even more momentous development — the demonetisation of high-value currency announced by the Prime Minister on 8 November 2016.

The brunt of the impact of both these events, particularly demonetisation, was borne by the National Banking Group (NBG) at SBI, which I was heading as the Managing Director.

One of the biggest challenges that came my way as Managing Director at SBI before I became Chairman was the impact and ramifications of demonetisation.

I heard the Prime Minister’s announcement to demonetise Rs 1,000 and Rs 500 notes while having dinner at the residence of Anil Khandelwal, Ex-Chairman, Bank of Baroda.

SBI Chairperson Arundhati Bhattacharya called me frantically, asking me to meet her at her residence immediately.

I reached her home at around 10.30 pm, and our anticipatory action started immediately.

The first step was to disable all the Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) and Cash Deposit Machines (CDMs).

The machines were also required to be reconfigured within the next two days to enable withdrawal of Rs 100 and Rs 50 notes, starting 11 November 2016.

The details of notes in the denomination of Rs 1,000 and Rs 500, called Specified Bank Notes (SBNs) were to be furnished to the RBI and arrangements had to be made to deposit the SBNs with the RBI.

Simultaneously, arrangements were also needed for the exchange of SBN up to Rs 4,000 at the bank counters.

There was no limit for deposit of SBN in the accounts where the account was fully compliant with the Know Your Customer (KYC) guidelines, otherwise only SBNs up to Rs 50,000 could be accepted.

Cash payment from a bank account over the counter was restricted to Rs 10,000 subject to an overall weekly limit of Rs 20,000.

Implementing all these instructions was going to be a nightmare for the bank as necessary modifications were required to be made in the accounting system to ensure compliance with the guidelines.

The biggest worry was, of course, that of managing the crowds at the bank branches when they would open on the first day after the announcement, that is, on 10 November 2016.

The SBI is not new to managing crowds, but this time we were entering into uncharted territory.

Line managers were told to take care of both the public and staff conveniences adequately in view of the expected rush at branches for exchanging the notes.

A warning memo was also issued that strict disciplinary action would be taken against any staff or officer engaging in any irregular practice.

Having handled the return of almost 30 per cent of the demonetised currency notes, SBI won huge appreciation from the public and all government officials who visited SBI’s branches during this period.

Considering that the decision had to be kept absolutely confidential till the last minute, it is apparent that even the RBI was caught by surprise and was totally unprepared to handle its fallout.

I am not sure whether the learnings from this largest-ever demonetisation exercise have been documented.

Hence, here I would like to mention a few things, which in my opinion could have helped avoid the chaos.

Firstly, the size of the new currency notes should have been kept identical to the demonetised ones in order to avoid the need for a change of cassettes in more than two lakh ATMs in the country, which was a hugely time-consuming exercise.

The service providers also did not have the requisite manpower and logistical support to finish this task quickly.

Further, they were also looking at this opportunity to make some extra bucks.

It was only through active intermediation by then Deputy Governor of the RBI, S S Mundra, between the service providers and the banks that the cassettes could eventually be replaced in a time-bound manner at a reasonable cost.

Since the focus was on quick re-monetisation, the new currency note of Rs 2,000 was brought into circulation.

This complicated the problem further as the currency notes of Rs 2,000 were of no use for small-value cash transactions that common people needed to make.

The next denomination was that of Rs 100 notes, which were not available in adequate quantity.

The absence of lower denomination notes was one of the most critical problems emerging from the demonetisation exercise.

During one of the review meetings of the Secretary, DFS, and Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs (who is now the RBI Governor) with SBI, and a few other banks, including the Chairman of the Indian Banks’ Association (IBA), the shortage of Rs 100 notes was a key point of discussion.

It was apparent that there was a great deal of confusion about the availability of Rs 100 notes.

The SBI’s assessment about the number of Rs 100 notes available was vastly different from the assessment of the RBI.

The confusion apparently arose in the process of converting millions into lakhs — one or two zeroes simply went missing!

I kept insisting that Rs 100 notes were in short supply and there was an urgent need to augment the supply of 100 rupee notes while also rapidly bringing into circulation the proposed new Rs 500 notes.

But this was easier said than done because all the note printing machines of the RBI were programmed for printing Rs 2,000 notes and required at least three weeks before the machines could print the new Rs 500 currency notes.

The availability of currency paper posed another major bottleneck, and it had to be imported.

Both the secretaries realised the problem and it was decided to immediately start printing the Rs 500 notes.

It was only when the supply of the new Rs 500 notes started improving and the process of change of cassettes at the ATMs gathered momentum that the situation began limping back to normal.

The second issue was that remonetising quickly by releasing the new currency notes was not the only problem to be tackled.

There were several states like Telangana and some in the northeast, which had an insatiable requirement of cash, wherein managing the cash logistics posed a big challenge.

There were frantic calls from currency chests across the country, and around-the-clock war-room was set up by SBI to alleviate the hardship caused to the people and try to meet all their requirements.

The storage and remittances of demonetised notes became another big headache because the RBI was not in a position to receive remittances from other banks and all the currency chests at the banks were getting choked.

It took almost one year for the RBI to receive back all the discontinued currency notes and count the same with the help of high-speed processors lent to it by SBI.

The biggest problem in managing the whole exercise was the announcement that SBNs would be changed up to a value of only Rs 4,000.

This measure was intended to take care of the common citizen, but the facility was grossly misused, as there was no restriction on the number of times one could exchange the banknotes.

In a country where the number of poor people far exceeds the number of people who had SBNs, it became very easy to hire people to stand in the queue for a commission and exchange notes.

To deal with this problem, the RBI issued instructions that a person could change the notes only once, and to ensure compliance, it was decided that the indelible ink used in elections would be used for marking the finger of every person at the time of exchange of the SBN, in a similar manner as is done at the time of voting.

Again, this decision did not take the crucial fact into account that there is only one supplier of the indelible ink, who is based in Mysore.

The IBA was instructed to coordinate the effort of procuring and distributing the ink.

The decision to use the ink and procure it urgently created so much panic that the IBA was reportedly given instructions by the Finance Ministry to airlift the ink from Mysore using a chartered plane.

However, the need did not arise, as the indelible ink was arranged from the local offices of the Election Commission.

One of the ostensible solutions offered for all these problems was that of giving a big push to digital payments.

However, the acceptance structure was inadequate and the country was dependent on the import of Point of Sale (POS) machines.

A POS machine has to be tested thoroughly for security reasons and configured before deployment.

Unfortunately, many officials were blissfully unaware of these limitations and thought that millions of such machines could be distributed as easily as if they were like supplying steel utensils.

Meanwhile, the goalposts kept shifting and frequent changes in the limits for withdrawal and deposit of cash, as well as reporting requirements by the RBI, became a nightmare for the IT departments of the banks.

However, the RBI had little choice in the matter as it had to respond and react immediately to the issues being raised by the public.

Interestingly, and rather inexplicably, the first-hand experiences emerging from discussions with the people who were forced to wait in long queues to exchange their notes clearly indicate that contrary to the general perception, by and large, there was no resentment on the ground against the demonetisation drive.

The divide between the haves and have-nots, and the anger against the moneyed class is so deep-rooted in the country that people were apparently willing to bear any inconvenience that would bridge this divide in some way and had the satisfaction that decisive action against black money was being taken for the first time in the country, as a consequence of which rich people were suffering.

There were reports of instances of wrongdoing by a few banks in exchange for SBNs, which had a bearing on the reputation of the bank staff.

Luckily such incidences were few and far between and were limited to two or three banks.

Considering that it was a mammoth exercise where currency notes worth approximately Rs 15 lakh crore were exchanged in a period of 45 days, the bank staff deserve all appreciation for their hard work and dedication while performing the critical exercise.

How Indian people could achieve this humungous feat in such a short time is a subject matter for research.

Excerpted from The Custodian of Trust: A Banker’s Memoir by Rajnish Kumar with the kind permission of the publishers, Penguin Random House.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article